“I want my friends to stop killing themselves,” retired Navy Corpsman Ciara Rayne said. “I want my friends to stop feeling alone and abandoned.”

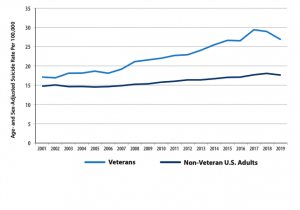

Federal statistics reflect Rayne’s concern. The rate of veteran suicide in the United States is over 50% higher than the rate for civilians, according to a report from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Biden Administration recently called this issue “a public health and national security crisis.”

“Since 2010, more than 65,000 veterans have died by suicide — more than the total number of deaths from combat during the Vietnam War and the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan combined,” read a fact sheet released by the White House last week. The press release announced a comprehensive new prevention strategy being implemented to reduce military and veteran suicide.

This includes using professionally-developed public service announcements and paid media promoted via social media platforms, according to the prevention strategy.

In conjunction with these efforts, last month the VA launched a nationwide ad campaign called “Don’t Wait, Reach Out.” The campaign encourages veterans to seek support before they reach the point of experiencing a mental health crisis.

Ads direct viewers to a website hosted by the VA containing a variety of suicide prevention resources — including a 24/7 crisis hotline, local resources and materials for family and friends.

The website first presents users with an array of personal struggles described with sentences like “I am bothered by traumatic memories” and “I miss being part of my community.” The site then customizes the resources it suggests based on which statements the user found most relatable.

“I really want us to make it safer and more survivable to experience a mental health crisis,” said Dr. April Foreman, executive board member for the American Association of Suicidology. Foreman said she is very familiar with the new campaign but was not personally involved in its formation.

The VA partnered with the Ad Council in crafting and implementing the advertisement strategy. The Ad Council is a prominent nonprofit known for iconic advertising campaigns like “Friends Don’t Let Friends Drive Drunk,” “Love Has No Labels” and Smokey Bear.

“When we ask people to call a crisis line, we’re asking for something that’s really hard to do,” Foreman said, pointing to the stigma many veterans feel reaching out for help. This makes creating an engaging communications strategy vital for an effective campaign, something Foreman said has been difficult in the past.

Thirty-four-year-old retired Marine Wes Rhodes said, “I put off getting support for a long time because I thought it was something that made me weak.” Rhodes served from 2012 to 2017 as a Special Operations Capabilities Specialist for the Marine Raiders.

As suicide rates worsened, Rhodes said a consensus emerged in the military community that “we needed to do something different” when talking about mental health.

Rhodes, who served as copywriter in the ad campaign’s development, said his team tackled this stigma by incorporating the voices of the veteran community throughout the creative process. As the only veteran involved in the campaign’s production, he said he also served as unofficial consultant.

His team gathered countless first-hand stories and experiences from veterans and active service members to inform decision-making. They then conducted internal testing with large groups of veterans to gauge the product’s effectiveness.

“We were really thrilled with the response,” Rhodes said.

The goal was to craft a message “grounded in real experiences” that makes veterans feel seen and understood, Rhodes said, instead of presenting them with stale “magic pill of happiness” messaging.

The ads depict veterans adapting to civilian life and experiencing gradually worsening symptoms of depression and anxiety. A narrator describes the temptation to disconnect and suppress emotions as an easy way out of dealing with mental health struggles.

“But you’ve never been interested in easy,” the narrator says. “Make no mistake — reaching out is hard. Do it anyway. You’re not alone.”

The ads visualize the strength it takes for veterans to reach out for help when they’re in a dark mental space. (Courtesy of Ad Council)

Thirty-eight-year-old Ciara Rayne served as a Navy Corpsman for five years. When she speaks with military friends struggling with mental health, she said she often appeals to their training. She said in the Navy they were taught never to enter dangerous situations without sufficient back-up.

“You go in there knowing your shipmates have your back,” she said. “Why does that vanish when we leave?”

Rayne expressed serious doubts that an ad campaign alone will effect meaningful change. However, she said if the initiative can help veterans recognize that getting help is not a sign of weakness, it will be worthwhile.

“The fact of the matter is, it’s the opposite of weakness,” Rhodes agreed. “Getting support is a lot of hard work. It takes a lot of strength and courage.”

Add comment