The day before Veterans Day, when military service members are honored, lawmakers listened to witnesses testify about veterans who go hungry, which one witness said was absurd to have to discuss in the first place.

Veterans Day celebrates and remembers U.S. military veterans and active service members. But many still wonder why their basic needs aren’t adequately met.

“No person should ever go hungry in America,” said Chair Jahana Hayes from Connecticut, in her opening statement to the House Agriculture Subcommittee on Nutrition, Oversight and Department Operations. “However, it is especially galling to see those who have dedicated their lives to serving our nation struggle to put food on the table.”

More than 37,000 veterans experienced homelessness last year, making up 8% of all homeless adults, according to a report by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“Military and veteran families have been allowed to go hungry on your watch,” Mia Hubbard, vice president of programs at MAZON, a Jewish organization fighting hunger, told lawmakers. “Your inaction has allowed this situation to persist for years…which has contributed to the worsening of diet-related diseases, loss in productivity and even spikes in suicide rates.”

In a report by RAND, a public policy think tank, researchers found that 14% of veterans who rated their health as “fair or poor” said they were also food insecure. The report also showed that 35% of veterans struggling with their mental health said they had limited access to food.

All four witnesses before the subcommittee expressed the urgent need to address this issue, which has persisted for decades. Shawn Lightfoot, a chef at Art-drenaline Catering in Washington, D.C., is taking matters into his own hands.

Lightfoot provides nutritious meals to veterans daily with hopes of alleviating the challenges some veterans face by fueling them with fresh fruits and vegetables, grains and proteins rather than fried and sugary foods.

“Think about what you’re putting in their bodies that help fuel them and help make them feel better and get them through the day a little healthier,” Lightfoot said in an interview.

At the hearing, Navy veteran Tim Keefe told lawmakers about his personal experiences with homelessness and hunger. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) cut him off after three months, forcing him to fend for himself.

He explained that he presented Department of Labor paperwork to SNAP officials, showing he was medically unable to work. But they told him he did not qualify for disabled status.

While experiencing homelessness and hunger, Keefe said he lost so much weight that he had to punch seven holes to his belt to keep his pants up. “There were more days than I care to remember where there was nothing to eat,” he said.

His emotional testimony drew the attention of lawmakers, who thanked him for his service and expressed appreciation to him for sharing his story.

Keefe explained that when he joined the military years ago, he never thought he would experience hunger. Now, he seems disturbed more has not been done to address this issue – one that he and thousands of other veterans, service members and their families face.

“When I joined the Navy in Boston, I was ready and willing to give my life for this country,” Keefe said. “And it seemed like during this time, I couldn’t even get a sandwich from them.”

Other witnesses and lawmakers discussed the Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH), which also prevents some veterans from qualifying for SNAP.

Rep. Alma Adams, D-N.C., said, “The Basic Allowance for Housing is currently considered as income when determining service members eligibility for SNAP,” presenting a barrier to some veterans if it pushes them over the eligibility requirement.

Adams asked Hubbard of MAZON why SNAP does not exclude the housing allowance as income.

“[BAH] is not counted or considered income for federal income tax purposes,” but it is for SNAP, Hubbard said. “For most federal assistance programs, it’s not treated as income. And so, it really seems to be an oversight. And it may have been unintended, but it’s persisted,” she said.

What Hubbard said may have been unintended has had major consequences for veterans. Nipa Kamdar, a registered nurse who works with veterans experiencing food insecurity, explained what she has learned from them, using pseudonyms.

“Some like Haley, a 35-year-old Army veteran and single mother of three, had tried to increase their food supply,” Kamdar said. “Haley applied for SNAP four times but never qualified. Ultimately, she stopped applying. She said, ‘I’ve been burned so many times. I don’t try it anymore.’”

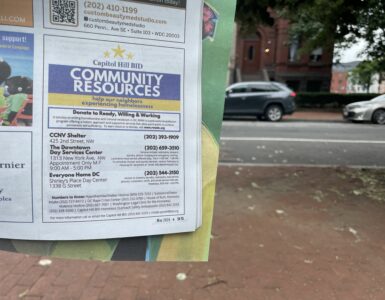

David Kurtz, executive director of Veterans on the Rise and an Army veteran himself, aims to help veterans in the D.C. area become self-sufficient. The program provides housing and meals as well as case management to assist veterans with employment, health care and their own bank accounts.

“Anybody who comes into our facility, we provide them with basic needs,” he said. “We also maintain a food pantry and clothes closet to support people in need.”

Both Kurtz and Lightfoot take pride in the work they do in the community. Lightfoot said many veterans respond positively to his program, and he hopes people treat them with the respect they deserve.

“When you think about a shelter, I believe that [people there] should be treated just like anyone else should be treated, and that’s how I try to treat them when I feed them,” Lightfoot said. “I want them to feel like they’re getting home-cooked meals.”

Add comment