Natalie Hopkinson has lived in Bloomingdale since 2000. She’s a professor of communications at Howard University. She’s raised two children in the neighborhood. She’s even written an ethnographic book about Washington, D.C.

But the neighborhood is still teaching her things, she said.

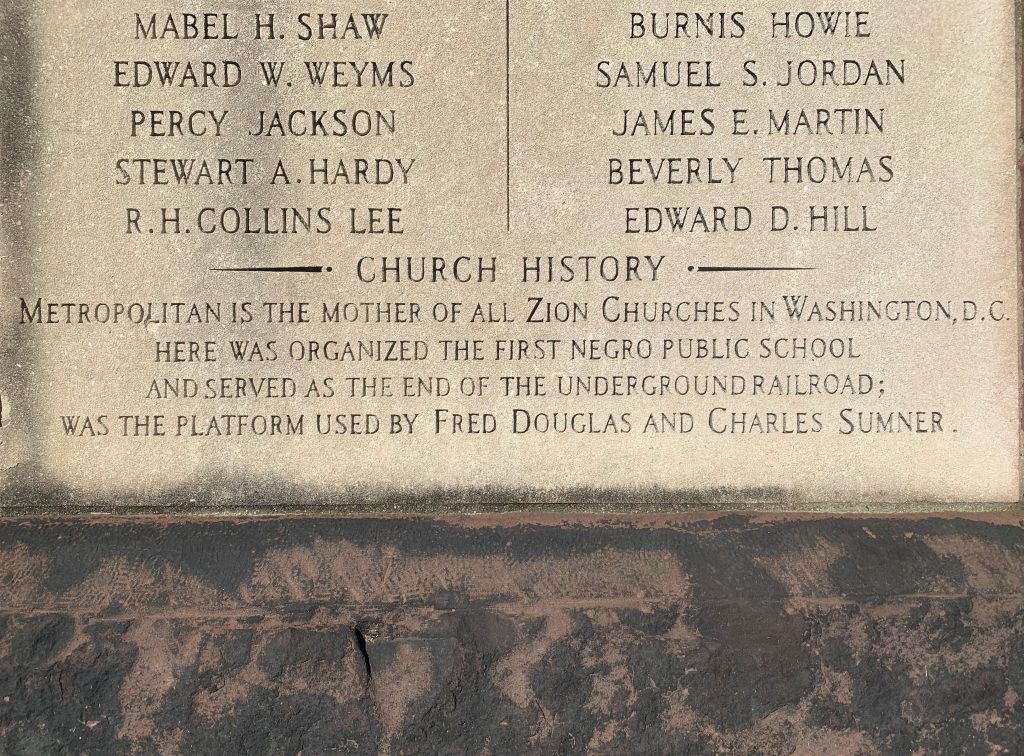

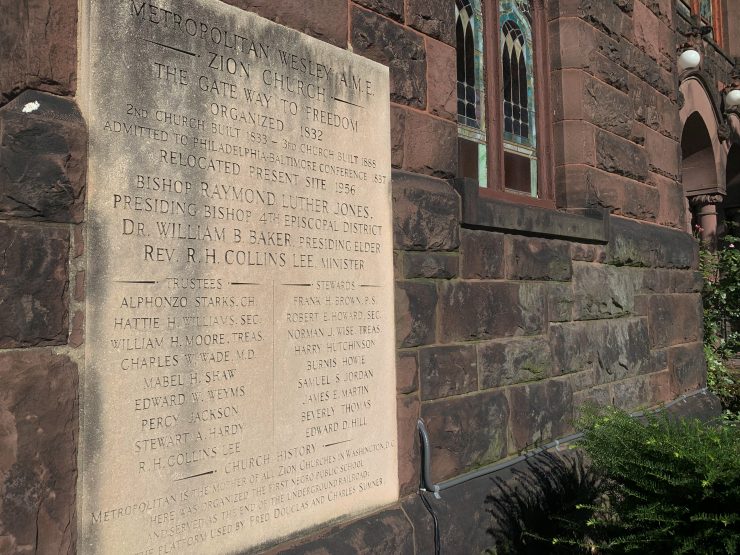

She was recently walking along North Capitol Street when she stopped in front of the Metropolitan Wesley AME Zion Church.

“I was last week years old [when] I learned that was the end stop in the underground railroad,” Hopkinson said. “Why don’t we know?”

The Bloomingdale Civic Association is coming to the end of a years-long project to help Bloomingdale students do just that 一 know about Bloomingdale and its history. The project is called Taking Village History to Our Youth and is spearheaded by Bertha Holliday, the vice president of Bloomingdale Civic Association.

“There was a need to really start grooming a future leadership cadre of folks who were going to be leaders in the community,” Holliday said.

So, she created a curriculum that addresses history, leadership and civic participation. Holliday originally envisioned the curriculum would be administered in schools and community organizations.

But with those venues now operating online, Holliday must recruit teachers and organizations to implement the curriculum while simultaneously making it compatible with online learning – all with mere weeks left in the project’s grant funding.

A shared space

It took Holliday and the Bloomingdale Civic Association (BCA) a year of grant applications before it won a grant from Humanities D.C. to fund the curriculum project. That was in May 2019.

The curriculum has 10 lessons that can be taught in a classroom or community setting, like Sunday schools. It also has 10 field trips. Some of the assignments ask the students to go on walks around their neighborhood, identify landmarks and street names, look them up and present their findings to their class. It also incorporates Bloomingdale Civic Association’s other historical resources.

Maybe, like Hopkinson, they’ll pass a landmark they had passed dozens of times before, but suddenly learn its significance. Or maybe they will learn the ways racism has shaped the neighborhood.

But long before BCA completed its first grant application, Holliday had been considering how to create a shared space for the next generation of Bloomingdale leaders long before BCA’s first grant application. She had noticed there weren’t many children playing together on streets and sidewalks.

She asked her friend Gwenn Bush-Hodge if she’d noticed the same thing. Bush-Hodge had young children at the time. She doesn’t remember the conversation with Holliday, but she does remember the neighborhood dynamic Holliday was wondering about.

Students in Bloomingdale often go to school outside Bloomingdale, Bush-Hodge said. They are driven to school and their extracurricular activities.

“Children do not see one another!” Bush-Hodge said in an email. “However, if the neighborhood schools were better, children would walk to school and get to know one another.”

This pointed Holliday toward making a curriculum on neighborhood history.

“That was the kind of common denominator,” Holliday said. “But it would also provide skill development to encourage the neighborhood kids to really have a sense of their having some real expertise.”

Bush-Hodge’s children are now 21 and 18 years old. Bush-Hodge isn’t sure that a curriculum on neighborhood history taught in different schools would facilitate the kind of collective identity Holliday hopes.

“In order for children in a neighborhood to know one another beyond a simple hello, they must have a shared learning environment,” Bush-Hodge said.

The curriculum as Holliday imagines it does culminate in a neighborhood showcase that would bring students and parents together.

Hopkinson has children about the same age as Bush-Hodge and said she encountered a similar dynamic when her children were younger. Hopkinson, however, is more optimistic about the possible outcomes of the project.

“The schooling piece is a lot,” Hopkinson said. “This [curriculum] could be something really powerful for Bloomingdale kids how they could bond around … tell the stories about the places around here.”

Hopkinson said one of the most surprising things she learned while working on the project was that there used to be tennis courts between Bryant and Second streets. When the neighborhood was desegregated, the white residents of that parcel dug up the tennis courts and built a structure between themselves and their Black neighbors.

“That is the sort of context that you really need to understand the new changes that are happening right now,” Hopkinson said. “The fears from the Black community are not invented. They are really rooted in historical truth – the way that white people have shared space with Black people.”

In one way, Holliday’s project is having to pivot in order to be compatible with the needs of the moment. But in another way, the completion of the Taking Village History to Our Youth curriculum comes at the perfect time.

A shared story

Holliday had originally planned to recruit schools and community organizations in spring 2020. But then the coronavirus pandemic delayed those efforts.

Uncertainty about how District students would return to school further delayed the project, but Holliday and her team are now back at work, digitizing the curriculum before the project’s funding expires at the end of the month. They will likely apply for more funding, as well.

They are also redoubling their efforts to recruit schools and community organizations. Their goal is to implement the project in January.

“I think the most challenging part is going to be really kind of this small group work,” Holliday said. “You can do that virtually, but can the kids really connect?”

But Holliday said the project does have one thing going for it that it didn’t in the spring – administrative interest.

Even before the protests following George Floyd’s death reinvigorated national conversations on the lack of Black stories in social studies curriculums, Ward 5 D.C. Councilmember Kenyan McDuffie introduced a bill that would create an African American history course within D.C. public high schools.

The bill is still in its early stages. Holliday said she’s spoken with Councilmember McDuffie about Bloomingdale’s efforts to find a place for its local histories in its classrooms.

Digital hurdles aside, however, Hopkinson said she still thinks there is room for a curriculum like Holliday’s. It gets students out in the neighborhood and away from their computers. The curriculum, Hopkinson said, gives students a sense of place.

“I know my chest puffed out a bit when I found out one of the endings of the underground railroad is like a block from my house,” Hopkinson said. “It gives a lot more meaning to the Sunday run. So, I think it’s great.”

This article was changed Sept. 23 at 1:30 p.m. to reflect the correct name of Natalie Hopkinson

Add comment