Two years have passed since Karen Lee stared down at her student’s empty desk for the first time.

The desk had belonged to Zaire Kelly, a 16-year-old student at Thurgood Marshall Academy Public Charter High School, who was killed just feet away from his Northeast Washington home.

Lee was his social studies teacher.

“It was really hard to be a teacher,” Lee said. “And this week has been extremely hard for me in ways the last two years haven’t been. I wasn’t allowing myself to feel my own grief.”

Four months after Zaire’s death, the school was thrown into another tragedy. Paris Brown, 19, was murdered in Southeast Washington.

Students at the Anacostia school know trauma. They know what it’s like to have their classmates ripped away from them and their sleep interrupted by gunshots.

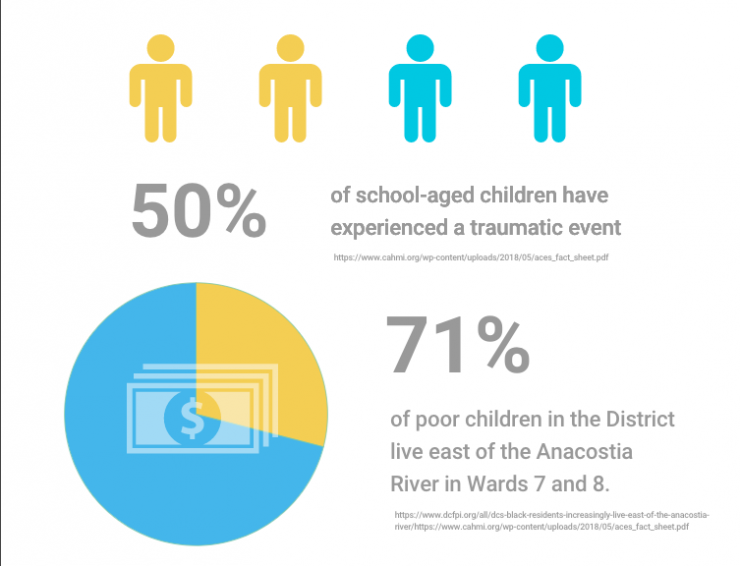

Now national data from the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative suggests nearly half of American children have experienced a traumatic event. Experts say growing up around substance abuse, domestic violence and poverty are common parts of childhood, according to data from Child Trends.

Children and teens can also go through trauma if their parents get divorced, if they experience the death of a loved one or if one of their parents is imprisoned.

Michael Blackson, 17, said guns and drugs are part of his daily life.

“Because I live in Southeast [Washington], it’s a really poverty-ridden area. It’s a lot of drugs on the street,” Michael, a senior at Thurgood Marshall, said. “Even though I live near a police station, they still shoot guns.”

The issue attracted the attention of lawmakers at an education subcommittee hearing in early September. Education experts and California’s surgeon general asked members of the House of Representatives to help school districts deal with students’ diverse needs.

Nathaniel Herr, a psychology professor at American University, said it could take a policy change to meet student’s needs. Schools can’t meet the needs of their students without the right resources.

“We ask schools to do so much and to expect schools to provide the types of therapeutic services students need is asking a lot,” Herr said. “If the resources aren’t given to the school, I don’t know how they could possibly manage it.”

Lee called for increased training for teachers and more mental health resources. She described professional development sessions about trauma-informed practices as “one-off” opportunities that teachers have to seek out.

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines trauma-informed practices as a “framework that involves understanding, recognizing and responding to the effects of all types of trauma.” Teachers want to infuse these practices into their classrooms, Lee said. Not all of them know how to.

“I don’t know that, as a teacher, I was fully prepared to know what I was doing,” Lee said about her career. She started teaching in D.C. schools 16 years ago. “I had a really steep learning curve.”

Gone unaddressed, trauma can snowball into greater.

“Exposure to trauma early in life does make you more prone to negative reactions to stress later in life,” Herr said. Adults who experienced trauma as children are at a greater risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

D.C. Public School officials know the trauma kids face at home is affecting the way they perform at school. The district this year launched Connected Schools, a network of campuses designed to serve not only as schools, but also as community hubs for health, employment and housing resources.

The schools are spread across five wards, with campuses in Columbia Heights, Lincoln Heights and Eckington. Ward 8 has the highest concentration of Connected Schools – Ballou and Anacostia High, Kramer and Hart Middle, and Moten Elementary schools.

“I look forward to working alongside our amazing educators to ensure that DCPS provides a great school in every neighborhood at every grade level and that our students are set up for post-secondary success,” said Lewis D. Ferebee, D.C. Public Schools chancellor, in a statement.

The school district also plans to introduce the LiveSafe app, software that allows students to share live updates from their commutes and report dangerous activity.

Students in violence-prone pockets of the city have long pleaded with officials to make their commutes to and from school safer. Zaire was gunned down on his way home from a college-prep course.

Student at Thurgood Marshall piloted the software in August.

“I liked the simplicity of it,” Michael said. He added the app would be useful during track season when he takes a bus home after late games and practices.

Michael also called on lawmakers to address the violence in his community.

As school districts across the county struggle to meet their student’s needs, Lee doesn’t want teachers to get left behind.

Teachers can absorb some of the trauma their students are experiencing, she said. Educators often take on the role of a counselor or even a parent.

And, they’re not immune to the grief students feel when one of their classmates die.

“I think that also has to be part of the conversation. How much we set aside our own needs to meet the needs of our school community,” Lee said about the staff at Thurgood Marshall. “I wonder if we need a teacher support group.”

Though, students are stepping up. The teens, in the wake of their classmates’ deaths, formed Pathways 2 Power, an anti-gun-violence group.

“They turned their grief into advocacy,” Lee said.

Add comment