By Oni Chaytor

For people who live in affluent areas of Washington, D.C., a trip to the grocery store is less than five minutes on foot. However, that’s not a reality for many district residents.

Often referred to as “food deserts,” certain areas of D.C. have limited access to healthy and affordable food. According the U.S Department of Agriculture, indicators of access include prevalence of grocery stores, vehicle availability and neighborhood average income.

D.C. has a notable amount of concentrated food deserts, 11%, according to research published by the D.C. Policy Center. Wards 7 and 8 are particularly vulnerable to food disparity with the largest percentage of food deserts, 51% and 31% respectively.

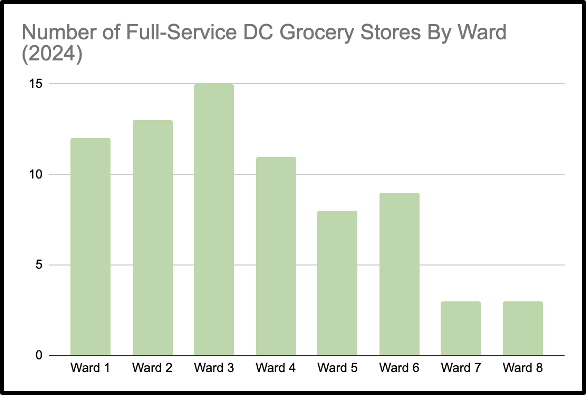

A 2024 report from D.C. Hunger Solutions, a non-profit working to fight against hunger in D.C., shows there were 15 full-service grocery stores in Ward 3 this year, compared to only three in Ward 7 and three in Ward 8. There was a two full-service grocery store increase between 2023 and 2024 for Ward 5, while the number of grocery stores in Ward 7 and 8 remained the same or experienced a small decline.

“There’s been lots of mapping done in the last few years. And when you look at census data, and then you do the map, on top of that, you see that the places most heavily populated by Black and Hispanic or people of color are the places with the least grocery stores,” D.C. Food Policy Council analyst Lawren-Christian Dolland said in an interview.

It’s a stark divide, according to D.C. Hunger Solutions director LaMonika Jones, who noted Anacostia has only one grocery store.

“Why is there only one grocery store? We just had a grocery store that opened yesterday in Ward 5. Ward five has several grocery stores,” Jones said. “Why is there a disinvestment east of the river compared to in other areas across the district?”

Multiple factors play a role in the increasing grocery store gap and food disparity crisis, including systemic racism. According to a 2023 Food Systems Assessment by DC’s Food Policy Council, a group of public and government food leaders dedicated to creating equitable food systems, 47% percent of Black district residents and 52% of Hispanic district residents were food insecure, compared to 14% of white residents. The assessment also notes that racially discriminatory practices such as redlining have contributed to the racial disparities in access to healthy, quality food.

Some food security advocates and policy analysts are pushing to use terms like redlining to describe disparities in food access versus “food deserts.”

“We don’t use ‘food deserts’ because deserts are naturally occurring parts of our ecosystem, and that there is life that occurs within our desert,” said Jones. “We elevate those definitions and those words and provide understanding, we use that in order to describe what’s actually going on in solutions.”

The practice of redlining has been an aspect of institutional racism that has prevented communities of color from accessing affordable housing. Supermarket redlining, which describes a practice of chain supermarkets that avoid building grocery stores in low-income and racially diverse neighborhoods, continues to explain how Black, Hispanic and other residents of color are disproportionately affected by food insecurity.

“Redlining is a practice that further segregated communities of color and those that are experiencing low income away from other parts of a given city or jurisdiction,” said Jones. “And those communities that were kind of boxed out of those areas or the areas that needed the resources the most.”

Given the food deserts prevalent in Wards 7 and 8, many residents are forced to travel outside of their neighborhoods to go grocery shopping. However, the lack of metro stops and accessible bus routes in the wards can make travel difficult.

“The majority of district residents utilize public transportation. If there’s not enough access to Metro stops, how is an individual supposed to get to and from the grocery store? They have non shelf stable foods that they’re purchasing, milk cheeses, things that need to be refrigerated,” said Jones. “If the time it takes for an individual to go to a grocery store is a lengthy amount of time, especially in warmer client climates and warmer weather, it is impacting the food safety of those items that they just purchased.”

As a result, many residents opt to shop for food at their local corner stores which often carry food items that aren’t as nutritious, leading to a multitude of health-related issues, experts say.

“Black people tend to have significant amounts of heart disease, hypertension, cardiovascular things, diabetes, a lot of the food related illnesses,” Dolland said. “And then when you look at a lower income, which means getting yourself to and from quality food, having the money to even get food, and so you go with what’s closer to you, which is probably of lesser quality, like at a corner store. And so now you’re just furthering the challenges, the medical challenges, the diagnosis.”

Experts on food insecurity argue that the food disparity crisis in D.C. is complex, so there must be multiple approaches and solutions in order to solve the problem. Black-owned food businesses have taken initiative to set up shops in areas with limited access to fresh quality groceries.

Amanda Stephenson, the owner of the Fresh Food Factory – a Black-owned ethnic grocery store — started her company following her dad’s cancer survival and has been committed to providing quality and diverse food options for residents in Ward 8.

“I wanted people in my community to have the same change in their trajectory, in the life expectancy that my father had when he had increased access and opportunity to make better decisions as it related to his health and well being,” Stephenson said. “What we look to do is to increase access to better quality food products, especially those that are ethnic foods, and, of course, healthy foods.”

Stephenson also highlighted the community-based approach many local food businesses like hers have, noting the fact that their fight to end food insecurity is driven not by corporate greed but by wanting to assist food insecure communities.

“We are part of the fabric. We’re more engrossed and ingrained and know the community and maybe have their best interests at heart,” Stephenson said. “I think that’s the sheer difference. A lot of times the smaller entities, they are looking at lasting and long impact on the community, and the big box stores [prioritize] the money.”

Another approach is incorporating the communities most affected by the issue into the decision making process. Tambra Stevenson, a Ph.D candidate at American University’s School of Communication – saw the need for a space where Black women who are passionate about food and nutrition can see themselves represented in the fight against food insecurity. This inspired the founding of WANDA: Women Advancing Nutrition, Dietetics, and Agriculture.

“I wanted women to see themselves as food sheroes and saving the community, meaning we can save ourselves. How important that is for self-esteem, for cultural affirmation, and just even in the circulation of the black dollar,” Stevenson said. “Women and girls make up the bulk of hunger around the world. So therefore, you know, the idea is, if we’ve not been leading, what happens if we actually lead the change that needs to happen?”

The end to the food disparity crisis involves approaching and tackling the issue from an intersectional viewpoint, according to advocates.

“It’s not just food itself. It’s not just, for example, putting your grocery store in a community and saying, ‘Oh, we’ve solved food insecurity.’ That’s not it. We have to look at a system-wide issue,” Jones said. “We have to look at the intersectionalities of food transportation, food affordability, child care, housing, all of those are players and factors that we have to consider when we’re thinking about food access and food insecurity.”

[…] to The Wash, Wards 7 and 8 hold the largest populations of food deserts (51% and 31% respectively). Further, […]

Better natural and nutritional food sources would prevent the rise of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and cancer within Ward 7. Ward 7 seems to be the forgotten section of the Nation’s Capital, being a food desert actually has an affect on the crime and violence that it perpetrated on these streets. While focus on

building a new stadium would bring jobs and revenue to this part of the city, the

physical health and greater healthy food options would go much further.