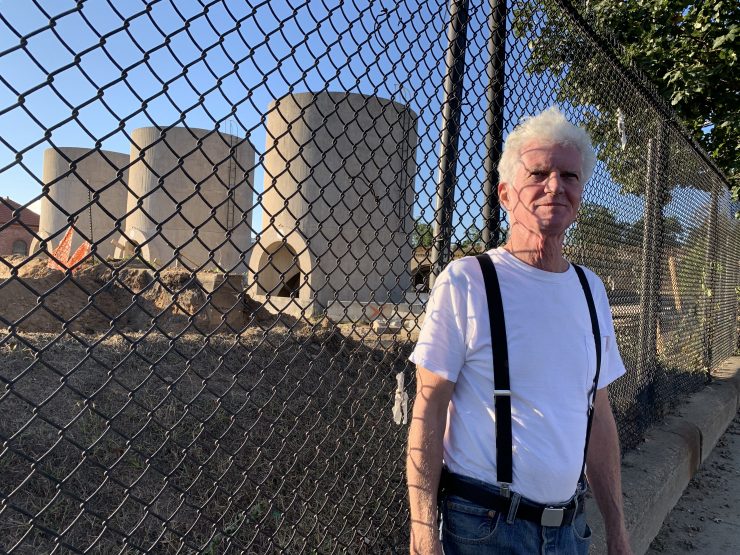

A demolition order hangs behind a wire fence surrounding the 25-acre McMillan Sand Filtration Site, which has been barricaded off since World War II. Deep furrows and piles of dirt surround the cylindrical towers once used for water filtration and now a historic landmark of the city.

All appearances suggest that the battle over one of the last big swaths of undeveloped land in northern D.C. is over.

But Kirby Vining, the treasurer for Friends of McMillan Park, is not ready to give up. Friends of McMillan Park, a group opposed to current development plans at the site, filed a last-ditch challenge against the demolition order in September, alleging that the city has not yet met the requirements for demolition, for example proving that they have the resources to complete the project. The suit is currently at the D.C. Superior Court.

It appears to be a Hail Mary after opponents to the project lost major battles over zoning and historic preservation. The legal battle and public discussions over McMillan have spanned more than half a decade and totaled more than 1,250 documents at the zoning commission and hundreds of public meetings. The city estimated the delays cost it more than 99 million in lost tax revenue and increased construction costs.

The plan for the development includes a medical office building, 146 townhouses, 500 apartments, a grocery store and a community center. McMillan Vision Partners, the coalition of developers in charge of the site, says on its website that more than 40 percent of the site will be open for park space. By breaking down the figures, the Wash calculated 20 percent of the residential units are affordable housing.

In July, the city and developers cleared the second of two major hurdles when the D.C. Court of Appeals upheld the D.C. zoning commission’s approval of the project. In April 2018, the Mayor’s Agent for Historic Preservation approved the mixed use development of the site, arguing that the benefits of the development outweighed the loss of sand filtration cells on the site.

Vining points to the piles of dirt. “They say it’s not demolition, but they wouldn’t do this at Mount Vernon,” he says.

Gilles Stucker, the Associate Director for Real Estate for the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, said vehicles at the site were doing preliminary testing on how to ensure that construction protected historic resources.

The developers did not respond to a request for comment about the suit in the D.C. Superior Court. Stucker said that he could not comment on pending litigation.

Vining, a former foreign service officer, has fought over the fate of the McMillan site, which sits less than a block from his home, since the 1980s. Vining said that he’s fronted some $250,000 of his own money into fighting the most recent development plan, some of which may be paid back through donations.

“Significant open park space, some development on a portion but nothing over five stories,” Vining said, sketching out his ideal use for the space. He said he and Friends of McMillan Park want an open bidding process and more creative proposals for the site, which, before World War II served as the first de-facto integrated park in the city.

When asked whether this dream has any chance now, Vining jumps into the intricacies of the latest suit. But he also admits that he has stopped going to farmers’ markets to petition support or aggressively soliciting new donations. “It’s up to the Court now,” he says, and he’s reluctant to ask people to pitch in when the end fate is so unsure.

Stucker, says for the city’s part, that the project is “closer than ever.”

The demolition order and impending development at McMillan may mark the end of an era in D.C. development disputes.

The city voted last week to make changes to its comprehensive plan to prevent similar litigation.

Activists or neighbors frequently sue over developments on the grounds that they don’t align with the city’s comprehensive plan, a blueprint for future development. This was a central contention in the litigation over McMillan and one of the reasons that the appeals court sent the project back to the zoning commission in 2016.

Some 5,000 housing units are tied up in litigation because they are part of planned unit developments, according to Cheryl Court, the policy director for the Coalition for Smarter Growth, a nonprofit that advocates for transportation and affordable housing in D.C., Virginia, and Maryland. The organization was part of a group that intervened in favor of the new amendments to the comprehensive plan.

Court says that the amendments to the comprehensive plan don’t make it harder to appeal but add “clarity” to the review process. She argues that developers have stopped applying for planned unit developments, which must go through the zoning commission and public hearings. “It’s cut the public out of the process,” Court said. “We’ve lost affordable housing.”

Vining, for his part, says that the previous plan allowed for adequate flexibility and community input.

Add comment