Alexandria next month will inaugurate its first Black woman as mayor, Alyia Gaskins, a moment that signifies both progress and persistent challenges faced by a city deeply formed by its racial history.

Gaskins’ leadership comes at a time when Alexandria’s neighborhoods, schools, and housing policies still reflect the legacy of segregation, restrictive zoning, and systemic inequality.

Throughout her campaign, the 35-year-old mayor-elect said she faced resistance over her age and relatively short time living in Alexandria.

“The biggest pushbacks that I got on the campaign were often an argument that she’s not old enough, and she hasn’t lived here long enough,” she said.

“I can’t help where I was born, and I can’t help when I was born, and so my age is actually my strength. It allows me to bring a new energy, and also I’m not new. I’ve lived here over eight years, but I chose Alexandria as my home,” she added.

As a working mother of two young children, Gaskins also addressed assumptions about balancing family life with leadership.

“I often was met with a very old-school mentality of, how are you going to do it all, or what’s going to happen to your children?” she said.

“I often was met with a very old-school mentality of, how are you going to do it all, or what’s going to happen to your children?” she said.

“Being able to do this alongside my kids and be an example for them of what’s possible is one of my greatest joys.”

Gaskins will take office Jan. 2 as Alexandria’s mayor, following her three years serving as a city council member.

While her historic election reflects shifting dynamics, questions persist about how fully Alexandria has moved toward acceptance and equality.

“I have a number of people sort of commenting on just our city’s history, where we’ve been, where we are, and sort of whether or not a Black woman could be accepted or rise to leadership in our city,” she said.

This reaction speaks to the larger issue of Alexandria’s racial history, which has shaped the development of key neighborhoods, the structure of its schools, and access to housing.

From the establishment of historically black communities to the legacy of segregation, redlining, and zoning practices, these historical patterns continue to influence community dynamics today.

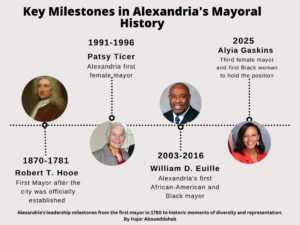

Gaskins’ election marks a historic moment as she becomes the first black woman to serve as mayor in the city’s history, building on the legacy of William D. Euille, who, in 2003, became Alexandria’s first Black mayor. It also raises questions about how Alexandria can address its deep-rooted inequalities and move toward a more inclusive future.

“I think it’s a wonderful achievement. It’s exciting for us to have an African American mayor, as it was very exciting for us to have Bill Euille when he was elected the first African male mayor for the city of Alexandria,” said Audrey Davis, director of Alexandria’s African American History Division.

“Of course there will always be challenges, but I’m sure she’s going to face those head on, and we’re looking forward to seeing the work that she does with the city.”

After the establishment of the town of Alexandria in 1780, numerous mayors led its governance through significant historical milestones. Robert Townshend Hooe, the newly established town’s first mayor, was a prominent merchant whose ties to slavery reflect the era’s complexities.

Historical records show that Hooe arranged an apprenticeship for an enslaved boy in 1800, highlighting the profound connection of slavery to Alexandria’s leaders and in shaping its early economic and social structures.

The Freedom House Museum located at 1315 Duke Street holds a chilling legacy behind its dilapidated brick structure. It was once the hub of Franklin & Armfield, one of the largest slave trading operations in the United States.

Enslaved individuals were held within its walls, awaiting their fate, whether to be sold at auction or shipped to the south, a process that tore countless families apart, some having never reunited again.

Between 1810 and 1860, traders like Franklin & Armfield trafficked nearly 450,000 enslaved people.

The pen represented despair for those held there but also resilience, as seen in the story of Mary and Emily Edmonson, enslaved sisters who attempted to escape slavery in 1848.

Today, the building stands as a poignant reminder of the city’s harrowing history.

“I think we’ve made tremendous changes, African American history is not just siloed at the Black History Museum or, say, the African American Heritage Park, but is represented in all of our historic sites,” said Davis.

“We also have social justice initiative, the community remembrance project, where we highlight our city’s history of racial terror, so we are committed to making sure the city is educated about those crimes, and that we are working to make sure that Alexandria is a welcoming community for people of all races, of all ethnicities, as they come to the city,” she said.

The legacy of slavery persisted long after its abolition in late 1865, with racial segregation shaping the city’s neighborhoods and daily life.

“Everything was separate, whatever you needed, separate schools, separate churches, separate restaurants, separate stores, separate areas to live in, separate ways of travel, everything,” said fourth-generation Alexandrian Lillian Stanton Patterson.

Patterson, who lived during the era of segregation, still vividly recalls how it impacted every aspect of life.

“When you rode on the bus, White people sat in the front and Black people sat in the back. And if the bus got crowded, White people could move and sit in the section where African Americans sat, but African Americans could not move up and sit in the other seats.” she said.

The segregation that defined daily life in Alexandria was a complex and deeply ingrained system. It influenced every aspect of life, from education and jobs to housing and transportation. For African Americans living in the city, this meant navigating a web of rules and restrictions that governed their lives back then.

“You get used to what it is. Now, how do you like it? It’s not fun. You don’t like it, but there’s little that you can do, until there comes a time when you said, “Enough is enough,” said Patterson.

“Segregation was a horrible thing, and you can still see the impact of segregation in neighborhoods or enclaves that are still primarily African American,” said Davis.

Significant milestones marked the fight for racial justice in Alexandria. The historic 1939 sit-in at the segregated Alexandria Library, one of the earliest of its kind in the country, challenged racial segregation in public spaces and set the ground for ongoing civil rights advocacy in the city.

In recent years, initiatives like “ALL Alexandria” have sought to address systemic disparities in areas such as housing, education, and economic opportunity.

These initiatives coincide with a historical analysis of restrictive covenants and zoning policies in Alexandria. A study titled, The History of Restrictive Covenants and Land Use Zoning in Alexandria, found detailed evidence on how policies like redlining, racial covenants, and urban renewal directly impacted Black communities in Alexandria.

These policies systematically restricted black people’s ability to build generational wealth. For example, early 20th-century racial covenants in neighborhoods like Rosemont explicitly prohibited property ownership by anyone who wasn’t white. These restrictions were extended to areas like George Washington Park and Uptown, reinforcing segregated housing patterns into the mid-20th century.

“I really commend the city for kind of taking a hard look in the mirror at what their past policies have contributed to the racial wealth gap and inequities,” said Jill Norcross, executive director of the Northern Virginia Affordable Housing Alliance.

“To be honest with you, just recognizing and doing the research on where those existed is really eye opening,” Norcross said.

“We have to really take a look at past practices and to make the connection for current residents about this is how we got here, and we have to kind of blame ourselves.”

Another study on zoning and segregation included redlining maps created in the 1930s classified Black neighborhoods as high risk for loans, which led to disinvestment and hindered home ownership. In later decades, urban renewal projects displaced black communities causing further disruption to community stability and economic growth.

“In Virginia, we can’t necessarily pass an inclusionary zoning policy. We can’t require a developer to put in affordable housing. Instead, we have to offer incentives for them to do that, or we have to offer voluntary programs,” said Gaskins

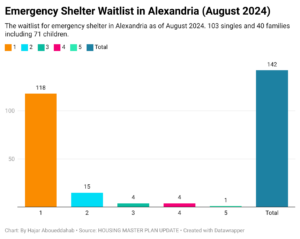

These challenges are compounded by the immediate need for shelter. As of August 2024, Alexandria’s emergency shelter waitlist includes 103 individuals and 40 families, including 71 children, underscoring the pressing demand for innovative solutions.

“I want people to see Alexandria as an example, not just of how we bring people to the table, because diversity is only one piece but of how we change the systems and structures that make it difficult for other perspectives, cultures, and people to engage and be part of decision making,” said Gaskins.

Gaskins upcoming inauguration has sparked both optimism and debate.

“I think it’s a very exciting time that we have another strong leader who will be inaugurated and will become our mayor in January. So, we’re all excited about that, and I think the possibilities are endless,” said Davis.

“Of course there will always be challenges, but I’m sure she’s going to face those head on, and we’re looking forward to seeing the work that she does with the city.”

“Of course there will always be challenges, but I’m sure she’s going to face those head on, and we’re looking forward to seeing the work that she does with the city.”

For some residents, her election signals a turning point, with hopes for transformative policies to tackle long-standing inequities, particularly in housing.

Housing prices are too expensive, said Andniello Rodriguez, a 20-year resident of Alexandria.

“I hope the new mayor will look out for marginalized people like us,” he said.

Rodriguez, currently rents a three-bedroom apartment for over $2,000 a month, he said despite working two cleaning shifts and his wife taking on part-time cleaning jobs, the couple struggle to meet their family’s basic needs.

Yet, not everyone views Gaskin’s election as a big shift in addressing systemic challenges.

“Having a black mayor is not as significant. It’s not as earth shaking,” said Patterson.

Patterson, who currently works as an educator at the Alexandria Black History Museum, said that the city works to push forward for a “diverse climate” while she refrains from using terms like equal rights.

“I don’t want to say equal rights, because that’s not what it is, to make sure that the climate of the city is diverse. Yeah, but is it equal? Nothing is ever equal, even in the best of times,” she said.

Patterson described equality as ensuring that everyone has fair opportunities, emphasizing that “equalism” is about making sure those opportunities are not restricted or diminished for anyone.

“When they say equal you want to make sure that everybody has the opportunity, and that the opportunity is not cut short. That’s what equal is,” Patterson said.

I welcome the new Mayor..From understanding her vision of diverse inclusion at the table, which includes perspectives from long lived Black residents who can speak for ones who feel uncomfortable at “The Table.”….I look forward to sit with her to discuss perception and perspective of marginalized/underserved and low income residents….We have had same group of people at decision making levels and keep getting same results for far to long!!