2021 has been one of the most fatal years in traffic crashes despite measures like Vision Zero and changing traffic safety reporting procedures. Advocates and residents want greater action.

Before 4B ANC Commissioner Evan Yeats came into office in 2019, he submitted his first traffic safety request for the intersection of Piney Branch Road NW and Dahlia Street NW.

It’s a busy intersection and, at the time, there were no stop signs at the intersection, just warnings to stop for pedestrians.

Yeats said people reported the intersection to traffic safety programs a while before then, and the community had worked with MPD to address enforcement.

Still, Yeats said nothing was done to fix the traffic concerns. Over a year later, in June 2020, 21-year-old Timothy Abbott was hit and killed by a driver while walking in a crosswalk.

Following Abbott’s death, DDOT added stop signs on Dahlia Street. But that’s just one intersection — and fatalities have continued to climb citywide.

There have been 39 traffic fatalities in D.C. this year, making it the most dangerous year for traffic in nearly a decade. “The failure is on all of the District government. Each one of those preventable deaths is on all of us for failing to move fast enough and taking the issue seriously enough,” Yeats said.

In the wake of these deaths, the city is speeding up the process of investigating traffic safety requests and considering greater use of automated traffic enforcement cameras.

But many residents and advocates wonder if the changes will be enough.

“They haven’t risen to the moment yet,” Yeats said.

Accelerating traffic safety requests

Yeats said the entire 4B commission has a consensus that traffic safety is a priority for their community. Additionally, he said it has always been a top concern for residents.

Yeats said one of the difficulties in addressing traffic safety issues is the lack of clarity from the District Department of Transportation on its processes for installing traffic calming measures on a variety of roads.

Ward 4 Councilmember Janeese Lewis George said in a statement to The Wash that residential streets lack the necessary measures to prevent speeding.

“The people of Ward 4 deserve to be able to safely walk, run, bike and drive in their communities,” Lewis George said. “But far too many of our streets are designed to prioritize commuters and speed over safety.”

Lewis George said she and D.C. Council worked to address these issues through fully funding the Vision Zero Act in the 2021 budget. Specifically in Ward 4 she said $1.7 million was secured for traffic safety improvements on Georgia Avenue, one of the most dangerous streets in the area.

Additionally, she said D.C. Council helped improve the system for making traffic safety requests. She said previously there was little to no transparency and the process for filing these requests was “arduous.”

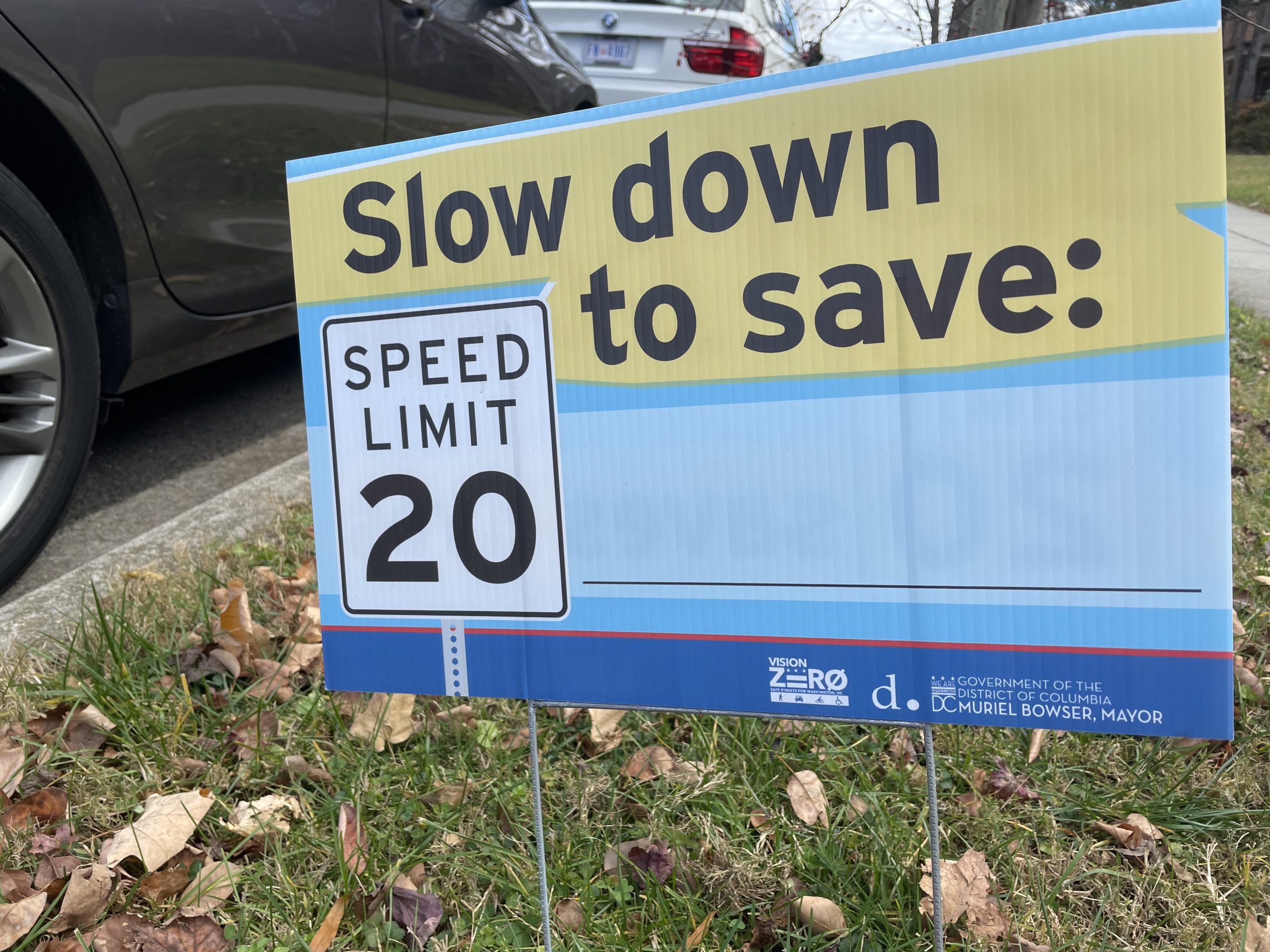

In October, DDOT streamlined the process and created a database accessible to the public to monitor requests. In a press release announcing the initiative, Mayor Murial Bowswer said the work to improve traffic safety is “urgent” and said DDOT would accelerate the process of implementing calming measures like speed humps and stop signs.

Yeats said it may be too early to tell if these measures will be effective but is skeptical it will create enough change. He said the new process is not transparent enough about the resolutions to traffic safety concerns.

“We aren't doing enough fast enough to physically reengineer our spaces for the safety of vulnerable road users,” Yeats said.

Yeats is also concerned about the timelines for repairs. Recently, he said he participated in creating a new cross walk in his community, a process that took three months total, which he said was too long.

Prior to Nov. 1, residents would need an ANC endorsement and questionnaire to submit a traffic safety assessment, according to DDOT’s Traffic Safety Investigation Service Request public database. DDOT changed this process to eliminate the need for endorsement.

In some areas Yeats said this could be helpful for residents who have less responsive commissioners. However, in other communities including 4B where there is a push to address traffic safety, he said the change takes away a level of oversight.

Lewis George said these were important changes, but there is still room for improvement in the system, including ensuring requests aren’t being closed out before the correct measure is taken.

“The underlying thread for all of this is a need to put people first in terms of the design of our roads, intersections and sidewalks so we can keep our community members safe.”

John Leibovitz, Brookland resident and CEO of Passage Safety, a start-up technology company focused on traffic safety, said he is particularly tuned in to safety issues in his Brookland neighborhood because of his two kids. He said one child is in sixth grade and has started walking to school and another child is in third grade and isn’t clearly visible to some drivers.

One issue he’s noticed in his own neighborhood is inconsistencies for the placement of stop signs. Over the years, he said resident requests have caused some intersections on the same street to have four-way stops while others don’t — for no clear reason. As a driver he said this can be confusing and ultimately dangerous.

Leibovitz said DDOT has been responsive to some of his concerns and is addressing some of those inconsistencies by adding four-way stops when necessary. But he said he believes there should be a greater look at traffic calming measures and infrastructure to prevent issues before they happen rather than being reactive.

Leibovitz said enforcement is an issue too. Recently, he said another driver behind him swerved into the other lane of incoming traffic, sped ahead and went through two stop signs.

“There were probably no repercussions for doing that,” Leibovitz said.

Enforcing traffic safety

Leibovitz testified at a recent D.C. Council public roundtable focused on automated traffic enforcement (ATE) cameras and traffic safety to discuss some of the work done by his new start-up Passage Safety. He said D.C. has 1,500 miles of public roadways, 18,000 intersections and 14,000 blocks but only 116 active automated enforcement locations.

He said it’s important to implement enforcement in neighborhoods where as a driver he’s witnessed dangerous and “unthinkable” behavior.

Leibovitz said during the hearing that the city should also consider less intense fines, equitable distribution throughout the District and state reciprocity to ensure out-of-state drivers are still paying traffic fines.

Hannah Neagle, a Vision Zero Campaign coordinator for the Washington Area Bicyclists Association, said the ATE program is an important piece of enforcing other strategies for calming traffic. She referenced other cities that have implemented ATE’s and said New York City has had a lot of success with its program.

Vision Zero and the bigger picture

The Vision Zero initiative, which aims to reach zero traffic fatalities or serious injuries in D.C. transportation systems by the year 2024, was adopted in 2015. But traffic fatalities have increased every year since then, except in 2019.

Earlier this year, the Office of the D.C. Auditor announced it would undertake a 10-month investigation into the initiative after attempts to curtail traffic fatalities have failed. Several advocates signed a letter in 2018 asking the D.C. Auditor to look into Vision Zero reading “if the Mayor-backed initiative created to eliminate traffic fatalities is not working, we want to know why and to what extent it's costing DC taxpayers," according to DCist.

Auditor Kathy Patterson said Vision Zero has been on her docket since then, but was moved up given the community interest, according to DCist.

Neagle said funding and implementing the Vision Zero Omnibus Act is a major focus. One of the challenges she said is DDOT’s capacity to address traffic safety. She said she hopes to see DDOT put more efforts toward traffic safety but the agency covers a wide swath of city issues.

Additionally, Neagle said it’s important to take an equitable approach to traffic safety. She said Wards 7 and 8 historically have more fatal crashes but receive less attention when implementing changes.

Neagle said she feels the mayor and the city have “turned a corner” and are more focused on slowing down drivers and preventing traffic fatalities. Additionally, she said there’s been clear public input that action needs to happen now.

Faith Hall, volunteer co-chair of D.C. Families for Safe Street, said on top of the 39 traffic fatalities and numerous injuries in the District, 314 people have been killed in traffic fatalities in the greater metro area.

“This is an epidemic, a hidden epidemic that has been ongoing in American society for decades,” Hall said.

Hall said her organization believes many traffic fatalities are preventable through lowering speeds, changing traffic patterns and adding other options of transportation.

Hall said the city has not reached its goal of eliminating traffic fatalities and is not doing enough to systematically solve the problem. She said DCFSS was pleased when Mayor Murial Bowser unilaterally decreased speed limits and when the Vision Zero act was passed, but she has questions about whether the program is adequately funded.

In 2020 D.C.’s chief financial officer released an analysis calling for more funding to Vision Zero. The report showed the Vision Zero total bill would cost $171 million over a four-year period to implement everything in the bill, including infrastructure enhancements and an expansion of ATE’s. The analysis found DDOT would need 17 new employees to effectively run these functions.

In May, Bowser announced $10 million would be reallocated in the FY2022 budget for safety improvement projects and the city ATE program. Additionally, in October she announced $345 million would be invested in streetscapes, trails and Vision Zero through the FY 2022 Fair Shot Budget. This total also includes the amount for Dupont Crown Park and a new South Capitol Street Trail to National Harbor.

But funding aside, Yeats, who also sits on the Vision Zero committee for 4B, said the goal of zero deaths by 2024 is still a good uniting goal, though he thinks the action taken by the city has been more performative rather than systemic change

“I'm really hoping and praying for DDOT to take ownership of [Vision Zero] in the next year and coming years,” Neagle said.

“Because unfortunately, we're not meeting the goals.”

Add comment