Air quality across the District has improved over the last few decades, but a recent NASA study warns Ward 5, home to the only two asphalt plants in the city, is more prone to air pollution than other parts of the District.

The study shows the inequitable distribution of poor air quality throughout the city, revealing wards affected by higher pollution levels have a greater risk of health problems.

The findings come as Eckington residents are fighting for greater equity in the city’s distribution of industrial land, with particular focus on those two asphalt plants.

New research shows that neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., with more people of color, are exposed to more air pollution and have higher rates of disease. https://t.co/Ny0aAHRkPD pic.twitter.com/IdG71hNA6w

— NASA Earth (@NASAEarth) November 9, 2021

Fort Myer’s asphalt plants

Eckington Civic Association president Conor Shaw wants to limit industrial land in the neighborhood that contributes to Ward 5’s poor air quality. Shaw has his eyes set on the asphalt plants, which sit on the northern edge of Eckington, surrounded by homes and businesses.

Fort Myer Construction owns and operates the two plants. Fort Myer has been in business for nearly 50 years, providing the DMV with infrastructure needs, including asphalt and road pavement.

“It’s striking that there’s only two asphalt plants in the city and they’re both located in this part of town,” Shaw said. “It’s also striking that the city, to my knowledge, does not have any permanent air quality monitoring locations in this part of the city.”

Asphalt plants release toxic pollutants into the air like formaldehyde and arsenic, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Exposure to asphalt fumes can cause health issues including headaches, fatigue, eye and throat irritation, and even skin cancer, according to the United States Department of Labor.

“It is easy for an untrained observer to have seen steam rise from our plants and potentially confuse that with smoke and/or pollution,” Chris Kerns, the vice president and general counsel at Fort Myer, said in an email statement. “Fort Myer’s state-of-the-art asphalt plants, both located in D.C., are tested annually by an independent, qualified laboratory and are in full compliance with Federal EPA and District of Columbia DOEE [Department of Energy and Environment] standards.”

“It’s important for people to understand that the city is authorizing facilities like this [asphalt plant] to put pollutants into the air, especially those that are known to be harmful,” Shaw said. “They’re only supposed to do that at levels that are safe.”

Kerns, the general counsel for FMC, pushed back on that claim. “Because our plants are outfitted with approved and redundant filtering systems which are consistently monitored, results show that our readings are far below the maximum allowed under even those tight standards,” he said in the email statement.

Shaw said the noise of the facility’s trucks and construction is also unacceptable. He said the plant operates late at night, early in the mornings and even on weekends. The designated truck route uses 4th Street NE, which runs adjacent to the facility, and is highly residential.

The plant is also next to the Metropolitan Branch Trail, “Northeast’s Rock Creek Park,” as Shaw likes to put it. The Rhode Island Ave-Brentwood metro stop is also just down the street.

“You definitely notice on this part of the trail that you’re inhaling other things besides clean air,” he said. “Land that’s next to a trail and within a half mile of a metro station in the core of the District is not an appropriate place for an asphalt plant.”

Sylvia Burch, who’s lived in the Eckington area for years, said the trail is where she goes to decompress. But Burch said the asphalt’s plant presence doesn’t go unnoticed.

“It’s smelly, it’s noisy and it doesn’t need to be in a residential area,” she said. “Use the land for something else, like housing or commercial use.”

Despite objections by some Eckington residents, Kerns said Fort Myer strives to create a safe place for local communities.

“As a 50-year-old locally owned company, and as a responsible citizen, we are committed to a clean and safe environment. We are proud to be the leader in the District of Columbia in the production of recycled asphalt and the building of green infrastructure projects,” Kerns said.

Eckington fights for a cleaner environment

Over the past four years, Shaw and other Eckington advocates crafted a comprehensive plan to help improve the neighborhood’s growth and quality of life. In 2017, they submitted a vision to D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson, pushing to use industrial land, like the area which Fort Myers sits on, for more housing, retail and commercial development.

“These changes we’ve pursued wouldn’t push anyone out, it would have made it clearer to folks that residential and commercial uses instead of industrial ones would be welcomed,” Shaw said.

Shaw said affordable housing was supposed to make it into the comprehensive plan, but he said Mendelson removed the recommendations made by Eckington residents and doubled down on his position that the District needs industrial land.

In April, the Eckington Civic Association proposed a letter to Mendelson, asking him to reinstate the ECA’s previous amendments for more housing. The letter stated that Eckington’s metro- and trail-adjacent properties are where D.C. must build affordable housing in order to achieve affordability, equity and environmental goals in the coming years.

“The continued concentration of Production, Distribution, and Repair (PDR)-designated land in Wards 5 and 7 poses racial equity issues, as the Chair has acknowledged in discussions about this Comprehensive Plan,” the letter pointed out.

Mendelson did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this story. But he did tell the Washington Business Journal in May that industrial land is still needed.

“No one wants a concrete plant or an auto repair shop near their house, but we need them…Are we all going to have to go out to the suburbs to get our cars fixed? At some point, we’re going to wake up and say, ‘Geez, there’s no land left for the warehouse or the concrete plant,’” he said at the time.

But the need for housing remains. Ward 5 resident and advocate Cynthia Carson said affordable housing is vital to local neighborhoods.

“There’s been so much history throughout these neighborhoods from racial covenants and unaffordable housing,” she said. “Local people can’t afford these places anymore, so something needs to change, affordable housing needs to be available here.”

An inequitable distribution of industrial land and air quality

Fine particulate pollution levels in D.C. have declined nearly 50% over the past 20 years due to a number of clean air laws. But the benefits of clean air are not distributed evenly across the District, according to the NASA study. And air quality data is limited, as there are only four air quality monitors in the city.

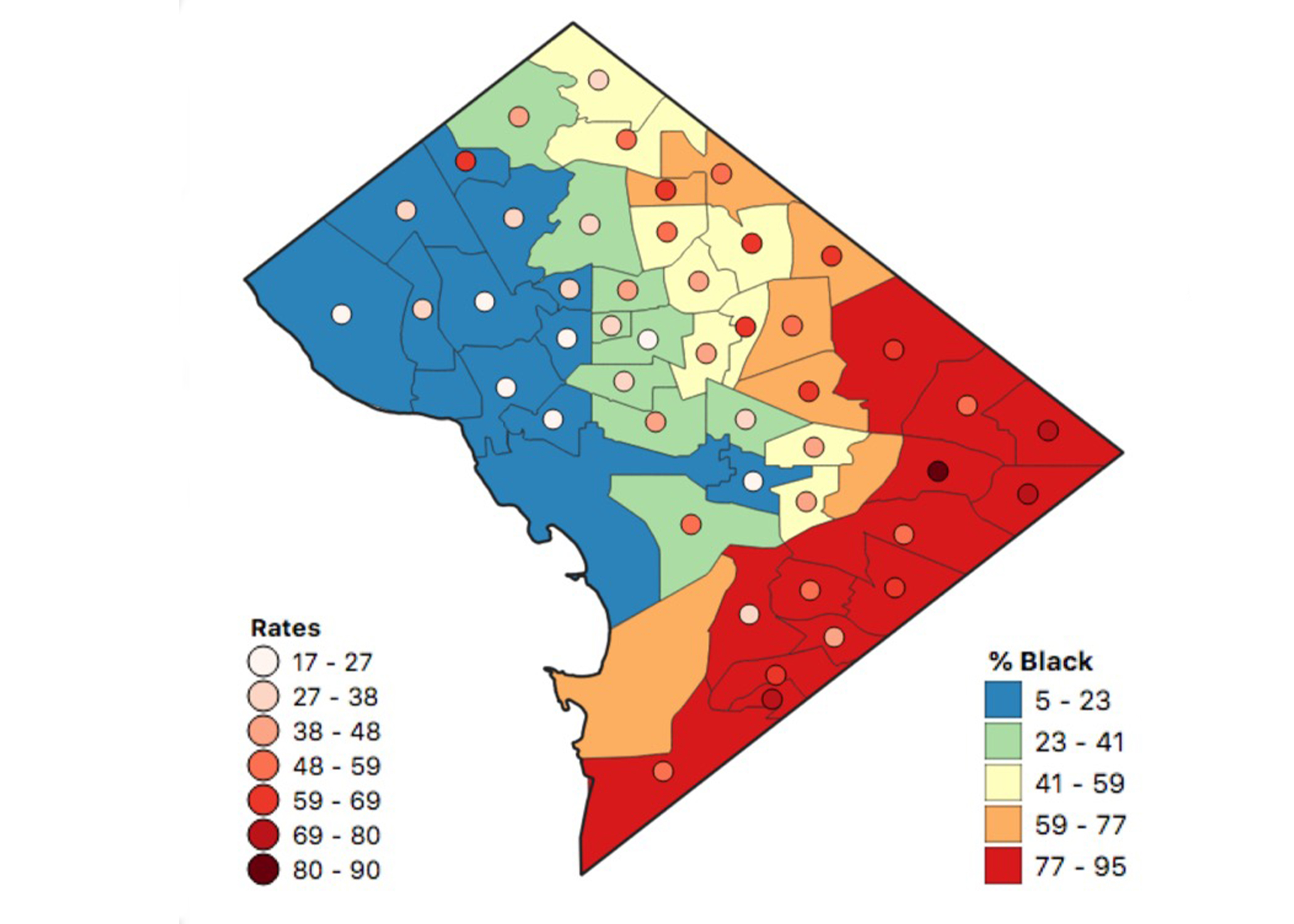

The recent NASA study also highlighted how those exposed to higher levels of air pollution in Wards 5, 7 and 8 are predominantly people of color.

As of 2019, residents living in PDR-designated land in Eckington are nearly 50% Black.

The map shows the percentage of Black residents in D.C. neighborhoods, with the dots representing the number of deaths attributable to air pollution per 100,000 residents. Those living in Spring Valley, Foxhall and other neighborhoods in Ward 3 are less likely to experience poor air quality. (Courtesy of Susan Anenberg/George Washington University)

“It’s a legacy of frankly racist decisions, having these facilities next to communities that were almost entirely Black,” Shaw said.

For the future, Shaw hopes to see proper use of industrial land in Eckington and other neighborhoods affected by poor air quality.

“We think the city should be doing a lot more to ensure residents aren’t being exposed to unsafe pollutants,” Shaw said. “Until we do something about this, the inequitable distribution of industrial land and the exposure to pollutants is just going to continue.”

Add comment