“Get inside. Stay Inside. Stay Tuned. Prepare Now.”

Those are the Department of Homeland Security’s four steps to limiting your exposure to fallout and surviving a nuclear explosion within the first 15 minutes of a blast.

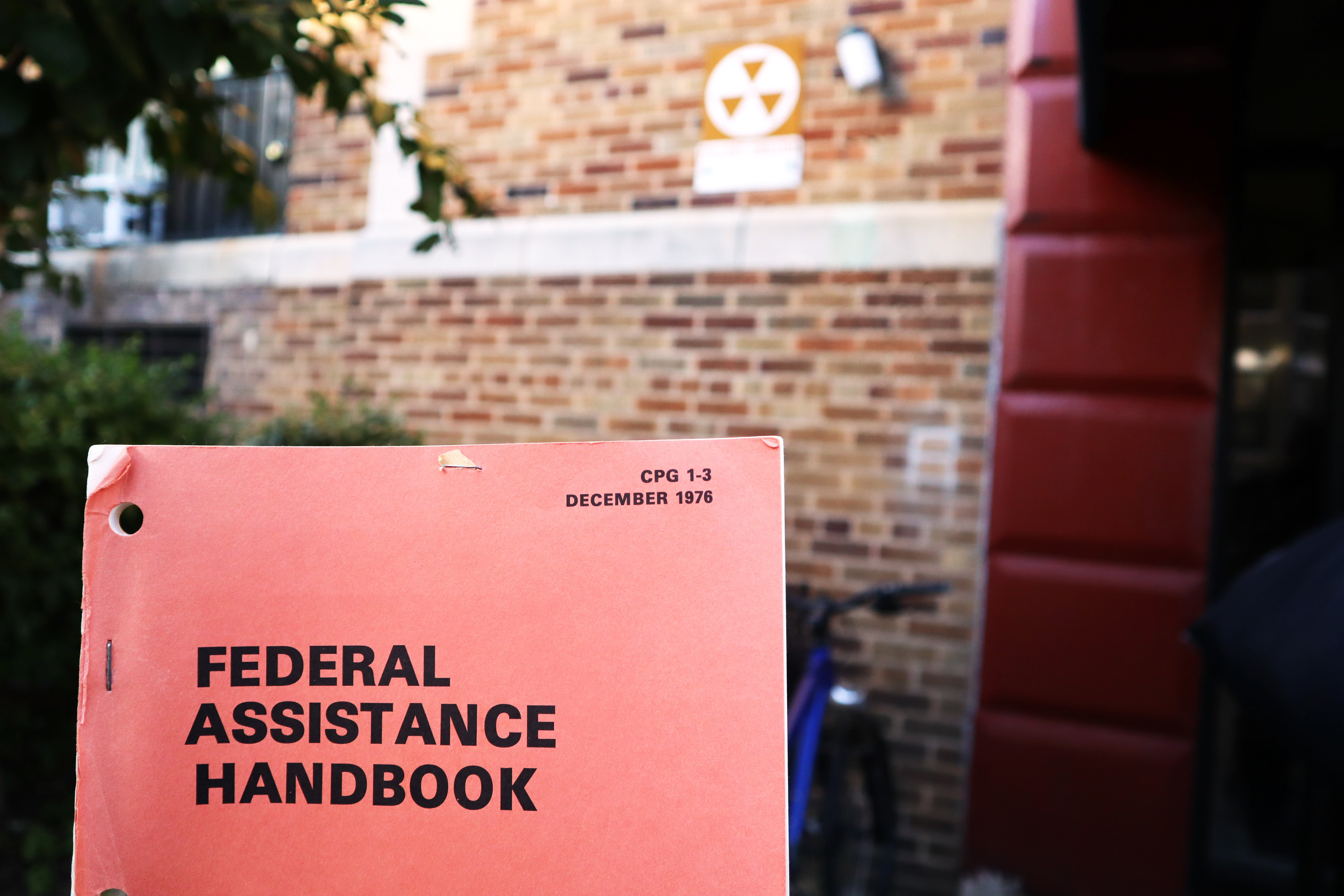

Shelter is key, with brick or concrete structures offering the best chances of your survival. Fortunately, the District’s fallout shelters are there for you.

Once you slide open the steel door and descend the cramped staircase to at least five feet below ground level, your new home awaits: a sturdy, compact place to wait out the fallout after the bomb. Equipped with a tiny kitchen, a bunk bed and a combination equipment room/bathroom, your fallout shelter is ready for you to hang out for two weeks, or as long as it takes. And don’t worry, a quality set of filtered air inlets and exhausts will keep you connected to the outside world and prevent your new space from getting too stuffy.

Thanks to remnants of the Cold War, just below ground level hides the District’s secret history of fallout shelters. Though no longer in the throes of the Cold War, the Doomsday Clock has been inching closer and closer to midnight. So, when that push notification finally comes and you need to find shelter fast, where will you go?

In a pinch, check out the shelter map on District Fallout. This blog, dedicated to the history and preservation of fallout shelters in the District, has compiled the locations of all the shelters. Some are now missing their signature sign, and some they have yet to verify, but others also still have their original signs affixed to their original structures.

The District gets ready

So why does the District have so many shelters?

The short answer is a fun doomsday prep concept that swept the nation and its capital in the Cold War: civil defense.

The book This is only a Test: How Washington D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War, written by David Krugler, chronicles the District’s history in uncertain times.

Most of these shelters were built in the fifties and sixties. “These are the years of unprecedented prosperity in the United States, at least for the middle class,” Krugler said.

The Office of Civil Defense, not fully funded by Congress, encouraged what Krugler called the “DIY approach” to doomsday preparation. With home ownership rates rising, civil defense campaigns targeted the white middle class.

“The civil defense message says: ‘There’s a possibility your home will be destroyed, but it might survive too,’” Krugler said. “‘And if it does, and you and your family survive, this is what you need to have in your home to stay on, to live.’”

The Office of Civil Defense Mobilization’s 1958 Annual Report described the 5-point National Shelter Policy as placing “joint responsibility for fallout protection on the Federal Government and the American people.”

The report said fallout shelters were vital to protecting the public. District Fallout estimates that 1,624 shelters remain in the District, even if some have been converted to a church, apartment complex or library.

The problem with living underground

At the 1960 Symposium on Human Problems in the Utilization of Fallout Shelters, Reuben Cohen of the Opinion Research Corporation addressed public opinion on the need for fallout shelters.

“Fully half of the adult public said they knew of nothing they could do to provide for own or their families’ safety before a nuclear attack,” Cohen said in his report. “Only 15% mentioned building a shelter or preparing a shelter space in their home as something they could do.”

A 1959 study revealed that the previous year, only 2% of District residents had prepared or built a shelter space.

Parkfair Apartments, Mount Rona Baptist Church on 13th and Monroe Street and the Mount Pleasant Library all used to be marked as safe havens from a nuclear apocalypse. Today, they still look like sturdy structures.

The catch, Krugler said, is that in the event of a nuclear apocalypse, the vast majority of those shelters would never have kept you alive very long.

“Absolutely not,” Krugler said.

For one, many of the fallout shelters financed in this era were built under structures that would not have survived the blast. Even if the building would have survived, the next problem was food.

At the 1960 Symposium, Syracuse University researcher Edward J. Murray addressed the needs of fallout shelters.

The Office of Civil Defense, Murray said in his address, hoped to stock shelters with “enough food to provide 2,000 calories per day per person,” assuming occupants were in the shelter for a two-week period after the blast. Unfortunately, in most parts of the country, this wasn’t a reality.

“Most of the fallout shelter space was not stocked,” Krugler said. “Fallout doesn’t go away in two days, or seven days or six months.”

Survivability, he said, is low.

Outside the shelter door

As President Trump prepares to leave the Cold War-aged Open Skies Agreement, memories of nuclear war fears slip back into the public consciousness. For District residents, fallout shelters—effective or not—are abundant reminders of these past fears.

Columbia Heights resident Sarah Dunesing has noticed the fallout shelter signs in her neighborhood in the past. Today, she said, the threat of nuclear weapons worries her.

“But I can’t think about it too hard,” she said.

District resident Aaron Chafetz has also seen the fallout shelter signs around Mount Pleasant. Though intrigued, he would not plan on using these old fallout shelters.

“Even if you go into it and you have this nuclear attack, what are you going to come out to at the end?”

Read portions of the Cold War-era documents referenced throughout the article to learn more about civil defense and fallout shelter design.

DC Fallout Shelters: Historical Documents

I WOULD LIKE TO BE PART OF THE TEAM THAT HELP WITH PUTTING FOOD AND EMERGENCY SUPPLIES BACK INTO THESE FALLOUT. ALLOWING A TEAM OF EXPERTS TO STABILIZE A BETTER CONSTRUCTION WITH ALL FALLOUT SHELTERS MAKING THEM MORE SUSTAINABLE FOR USE IN CASE OF A NUCLEAR ATTACK. THIS SHOULD BE DONE WITH UTMOST IMPORTANCE.