By Emily Sohl

As tariffs threaten to drive up prices on everything from bananas to backpacks, and fears of a recession loom, many Americans wonder how they’ll continue to afford necessities.

According to the Huffington Post, major retailers are already warning that shoppers will see emptier shelves and higher prices, especially for essentials like clothing and school supplies. ABC News also reported that items such as laptops, toys and coffee could see price hikes.

But amid this economic uncertainty, a different system is quietly taking root—one built not on profit but on cooperation.

Since the start of the pandemic, many communities in Washington, D.C. have embraced what’s known as the solidarity economy: a network of grassroots efforts centered on meeting people’s needs.

“The solidarity economy is a name for economic practices that prioritize people and planet over profit,” said Dr. Stephen Healy, a professor at Western Sydney University and co-author of Solidarity Cities: Confronting Racial Capitalism, Mapping Transformation. “Democratic inclusion, cooperation, and sustainability are kind of the guiding commitments.”

This growing movement can be seen across Washington, from community gardens donating fresh produce to mutual aid hubs like Remora House DC, where volunteers provide cash, supplies and emotional support to those most in need.

“It’s a very simple gesture but incredibly powerful,” said Healy.

“And it’s kind of insisting that actually we can arrange to take care of one another and meet one another’s needs on a basis of voluntary cooperation.”

As the cost of living climbs and economic support systems falter, organizers say this way of living—rooted in mutual aid and connection—matters now more than ever.

“We’re going to need to figure out how to show up for one another and be sure people are fed and getting access to the medical care they need,” said Shannon Clark, co-founder of Remora House DC.

A Garden That Gives Back

At Newark Street Community Garden, nestled in Northwest D.C., more than 200 garden plots sit side-by-side, each tended by community members. While the garden offers people a chance to try their hand at growing vegetables, it’s also a hub of giving and connection.

Ryan Fitzgerald, president of the garden, said hundreds are on the waitlist for a plot. “We want a lot of people in the city to have the opportunity to try gardening,” he said.

But the garden is about more than just trying a new hobby. Members volunteer their time and donate their harvests to So Others Might Eat (SOME), a nonprofit that provides food and services for people experiencing poverty. The garden even has a dedicated donation plot, but many gardeners give away their best produce from their beds.

“People are pretty good about it, they know where it’s going,” said Fitzgerald. “They’re not digging up a bunch of random junk and giving it. I have noticed people will have nice lettuce, salad things, things that can be cooked.”

The connection with SOME helps gardeners be more intentional about what they grow and give, ensuring their donations become nutritious meals.

And beyond food, the garden itself is a space for building community. Interest in community gardens grew during and after the pandemic, according to a study in Urban Forest & Greenery.

“I think people were a little more focused on their home neighborhoods, their communities, being closer to home and being outdoors,” said Fitzgerald.

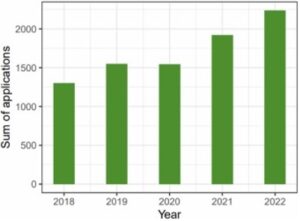

Applications reported by 28 garden coordinators, by year. Source: ScienceDirect

Even those without plots stop by to walk through, admire the plants, or chat with gardeners.

“It’s interesting, you can walk through the garden and see hundreds of different plants,” said Fitzgerald. “There’s tons of birds, birds love this place.”

And for those who do have plots, the space has become a social hub.

“It’s a great place to just hang out,” Fitzgerald added. “I spend way less time on my plot than I do just walking around, helping people out or just seeing what people are up to.”

Mutual Aid, Built on Trust

Remora House DC began with just a sewing machine and a few packs of sanitizing wipes during the early months of the pandemic. Clark, a grad student at American University, co-founded the mutual aid group to help unhoused neighbors survive the crisis.

“Starting from sewing masks and handing out sanitizing wipes, it’s really, really grown over the years,” Clark said. “We’ve just kind of responded to the needs as they’ve been brought up to us.”

Today, the group provides everything from moving help during encampment sweeps to emergency rent support. At the start of each month, they distribute $150 to 15 people—no strings attached.

“Whereas a lot of people doing that direct cash aid would be like, ‘well it has to go to food’ or ‘it has to go to medication,’ we don’t set those parameters around it,” Clark said. “That’s just our way of giving people that autonomy over determining their own needs.”

What sets Remora House apart is its long-term commitment. The organizers work to build genuine, lasting relationships with the people they support.

“We see at the core of what we’re doing is the relationships,” Clark said. “We prioritize continuing on that kind of support even when folks do get moved into housing.”

Clark sees mutual aid as more than charity or a response to immediate needs. It’s a push against the isolation and inequality embedded in capitalist systems.

“It’s not just making sure people have hand warmers when it’s cold out,” Clark said. “To us, it’s a revolutionary act to build that kind of community and connection with people in a world that’s intentionally built to break down those kinds of connections.”

She believes that collective care isn’t just helpful—it’s necessary.

“Because you’re going to need that help one day,” she said. “Mutual aid is all about how we all need each other. We’re paying into building a community that can be there for us when we need it.”

A Growing Movement

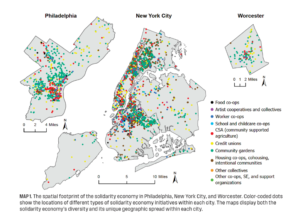

The solidarity economy continues to grow in large and small ways — from food co-ops to tenant unions to neighborhood gardens. In Solidarity Cities, Healy and his co-authors explore examples of these networks in New York City, Philadelphia and Worcester.

Source: Solidarity Cities: Confronting Racial Capitalism, Mapping Transformation

While his research documented more formal mutual aid networks and cooperatives, Healy said many acts of solidarity happen informally every day, often in ways that can’t be tracked.

“How would you put them on the map? They’re everywhere,” he said. “They are coextensive with the space in every human community. The metaphor we’ve used is that these are the fruiting bodies and that the mycelial network of solidarity is everywhere and beneath the soil.”

To Healy, these everyday gestures and relationships point toward a future not built on the collapse of capitalism but on intentional transformation.

“And so rather than imagining that we need to wait for capitalism to implode under the weight of its own contradictions,” Healy said, “we can bring to practice a post-capitalist politics now.”

Healy believes this shift will only become more necessary and visible in the years ahead.

“As things become more socially and ecologically precarious, my suspicion is that practices of cooperation and mutuality will become more significant,” he said. “And every time that happens, it’s a space for people to learn that it is actually possible.”

[…] of alternatives US residents need to know about in order to survive these times. Here’s how Washington, DC, is working on […]