A week after the drowning death of a 20-year-old woman in Little Falls, Maryland kayakers find themselves stunned and shaken as they reassess their own safety protocols while traversing Montgomery County waterways.

The accident was mourned as an anomalous tragedy by Maryland kayakers, who are now reckoning with potentially hazardous yet common practices on the water and weighing giving up whitewater kayaking altogether.

Ella Mills, a Columbia University student, was on a trip with her school kayaking club along the Potomac River on September 17 before her vessel capsized in an area under the jurisdiction of the C & O Canal National Historic Park.

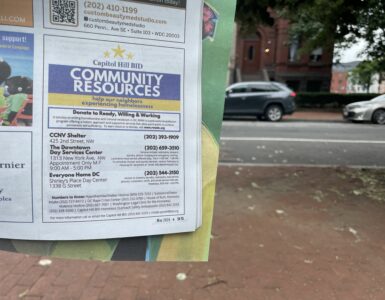

The incident occurred in a section of rapids along the Potomac due east of Maryland’s Brookmont neighborhood and the Lockhouse 6 landmark and dwelling space. Kayakers flock to this spot where a parking lot across from the canal and town path gives way to a Potomac River inlet alongside the Clara Barton Parkway.

Montgomery County Fire and Rescue Services Public Information Officer Pete Piringer said Mills attempted to swim but was caught in a section of rapids where she remained trapped until rescuers arrived.

“One of their boaters — kayakers — became distressed and experienced a problem,” Piringer said. “[She] essentially was brought under the current and underwater, trapped under a rock and unfortunately presumably drowned as a result.”

An investigation into the incident, which was handed over to the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, is ongoing. Officers have yet to determine how Mills became trapped, but department public information officer Kristina Saunders said rescuers believe her clothing was ensnared by a rock.

The C & O Canal, a winding waterway and accompanying walking path, stretches 184 miles long and connects Cumberland, Maryland to Washington through what was originally built as a commercial channel adjacent to the Potomac. Kayakers frequent canal property, using it as a staging area to enter a variety of rapids on the nearby river.

The canal and the Potomac both saw dozens of accidents, including drownings, between 1989-2023, according to the National Park Service, but last week’s incident stood apart because it occurred in a segment of the river not known for treacherous currents.

Jeremy Blum, a kayaker who regularly paddles near the accident site, said the river segment in question is a designated Class II rapid, involving “Straightforward rapids with wide, clear channels,”

To Blum — cautiously clad in a helmet and life preserver— last week’s incident represented an aberration in an otherwise safe region of the Potomac.

“This run, typically, is one even beginners go on, and they’ve been going on many, many years,” Blum said. “It seems to me, based on the descriptions that I’ve read, that it was very much a freak accident, and she just ended up being very unlucky in the way that she ended up trapped.”

As a 10-year veteran of Montgomery County rivers, Blum is reluctant to give up his hobby and does not find fault with any individual or group for Mills’ death, but he is willing to acknowledge a cavalier attitude toward river safety persists among some whitewater kayakers and hopes to see a cultural shift.

“I wouldn’t blame anyone,” Blum said. “What’s happened is the kayaking community has been thinking about the accident and thinking about what could’ve been done differently to try to avoid it.”

Part of what puts kayaker at risk — even in calm waters — Is a sense of invincibility and a pension for showmanship which lifelong Maryland resident and avid rafter Matthew Bothner said leads kayakers to attempt a variety of daring stunts, often resulting in near-disastrous capsizes.

To Bothner, a lethal accident in Little Falls was only a matter of time away.

“I’d believe it could happen,” Matthew Bothner said. “People kayak down here all the time. I see them doing their crazy flips. Sometimes I even see it where they have to help each other get back in because sometimes they’ll flip themselves under water.”

Bothner said he tried to be abundantly cautious when out on the water. He said despite his wealth of experience fishing from his own vessel, he no longer feels safe on the Potomac after last week’s incident.

“I can absolutely see someone getting in over their head out there,” Bothner said. “I have a fishing kayak personally and I take it out on a lot of ponds and lakes, and I don’t feel comfortable taking it on the Potomac River. I wouldn’t discourage anyone away from a sport, but I would make sure that they’re cautious before they get into it.”

When reflecting on his own activities, Blum admitted he often rafts solo and said the accident on the Potomac last week opened his eyes to the dangers or kayaking solo, considering deadly accidents can happen even in large groups.

Blum urged novice kayakers to take aquatic rescue courses and explore the Potomac in groups.

“One of the recommendations would be to always paddle in a group, make sure there are people in the group who really understand the section of river that you’re going on, and take a water rescue class.”

The National Park Service published a list of safety recommendations for whitewater kayakers, including checking water levels and avoiding rocky areas.

The National Park Service could not be reached for comment.

Please note that I never “acknowledge(d) a cavalier attitude toward river safety persists among some whitewater kayakers and hopes to see a cultural shift.” I think that kayakers take river safety very seriously, in general, and I do not see a need for a cultural shift.