An alley in Northeast D.C. is home to an art studio aptly named – Kucheh, meaning

“narrow alley” in Farsi. Mina Jafari, who co-owns the studio with her husband, opens

Kucheh to visitors every Saturday. Iranian themed art pieces don the walls, and t-

shirts and other accessories stare back at visitors with their unibrow eyes.

Guests are welcomed with hot cardamom tea — traditionally served in Iranian

gatherings — as a vinyl record player softly plays the sounds of 70s psychedelic rock

superstar Kourosh Yaghmaei. The familiar sights and sounds of Iranian traditions

have created a welcoming space for local diaspora Iranians – and a safe, calm place to

discuss a violent, ongoing feminist uprising 6,000 miles away.

In September, Iranian police were accused of beating 22-year-old Jina Mahsa Amini

to death for allegedly wearing her hijab incorrectly. Iranians regularly head into the

streets to protest the brutal way she died and challenge the oppressive norms society

has imposed on them. Locally, Iranians gathered in the streets of the District to

support the movement with folks from all generations and genders showing up to

protest the authoritarian regime Iranians have faced for decades.

While the physical distance made supporting the movement on the ground difficult,

some locals, including Jafari, refocused their feelings of helplessness by getting

creative.

“I’m an Iranian-American woman living in D.C., trying to make a difference, and I’ve

found that if I really want to make a difference, why not use the skills I have?” said

Jafari.

Jafari has always centered her art around justice – the feminist uprising in Iran being

no different. Her American upbringing included trips to Iran, but despite regular

visits, the distance from her motherland felt omnipresent.

“Growing up, I always wondered – ‘why do I have to be so far away from my

family?’ When there’s a funeral or a birthday or a wedding, the distance always

creates anxiety, and my art has been my way to kind of satiate that yearning for home,

but to also express myself and who I am here.”

She describes herself as always having been creative, and despite an academic

background in politics, she ultimately followed her passion and is now a full-time

artist.

It’s not lost on Jafari that the timing of her studio opening coincided with the killing of

Jina Mahsa Amini, influencing how the space is used and how some of her most

recent pieces came together and were developed.

“In the beginning, when this all started, and protests were picking up, people were

coming here because we were offering screen printing of our art on t-shirts, so people

would stop by before heading to protests,” she said. “There’s been so much art coming

out of this movement and it’s been nice to see what I have to add to it.”

While many have been supportive, community infighting has caused Jafari to receive

pushback from other Iranian-Americans.

“There has been a witch hunt. I feel like there has been a section of the community

who definitely has been misinformed and kind of had their emotions manipulated, so

they think there are enemies among us, within our own community,” she said.

While Jafari has had a few experiences of harassment, she expressed, “It doesn’t deter

me because it’s nothing compared to bullets. I can face a few negative comments, but

I do think it’s unfortunate. I want us to not lose that sense that we’re all in this

together, and really to not fear one another. It’s just gonna break down our energy.

Even now, talking about it, it sucks energy out of me.”

As weeks passed and the movement grew stronger, new faces at Kucheh turned into

regular visitors.

“Kucheh has kinda been a community center, a refuge, a place to create art, a place to

just hang out and have our creative juices flowing,” Jafari said.

Some folks stopped by for a cup of hot tea and conversation so frequently that they

began to refer to themselves as the Kucheh Kollective, self-described as “D.C.

creatives with eyes on the streets of Iran.”’

They meet regularly at Kucheh to discuss life, the revolution, and ways that they can

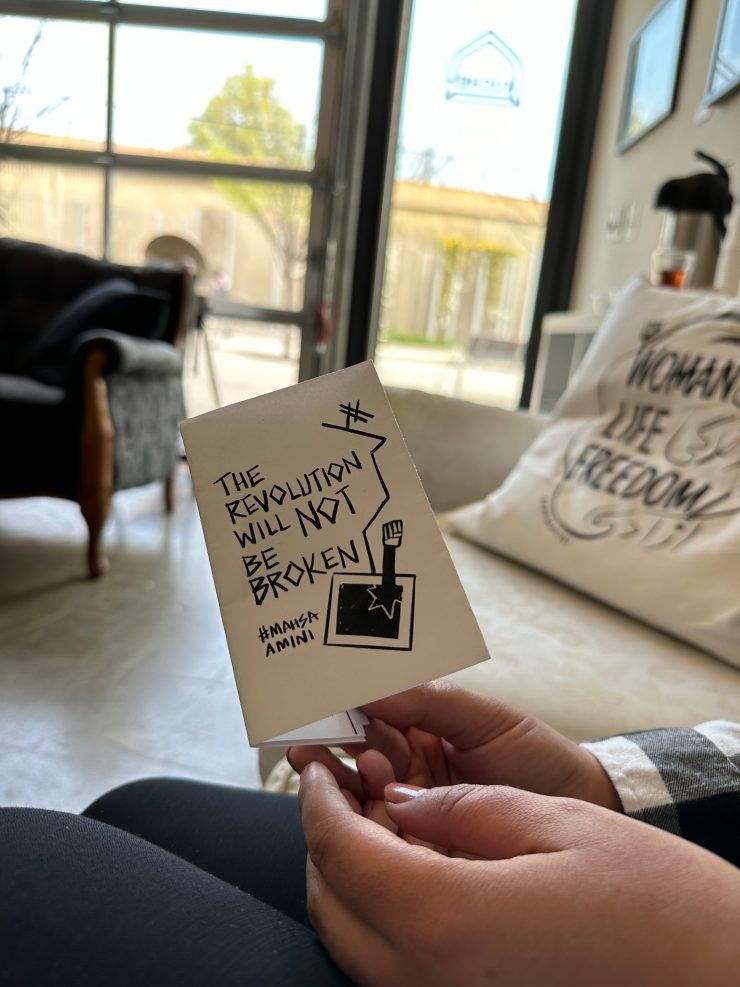

creatively respond to it. One of their ideas included making a free, downloadable zine

to explain the ongoing movement and how it started, with the goal of helping local

folks understand what is going on in Iran and how they can help.

“We all have to search within ourselves and figure out, ‘what does women, life,

freedom mean?’ The revolution is not just in the street. The revolution is in our minds

and hearts, and what we have to shift is a mentality as well as it is a system of

government,” Jafari said.

Ryan Aghabozorg, a 34-year-old D.C. resident hailing from Texas, joined the Kucheh

Kollective after becoming a regular visitor at the studio.

“I think it’s an opportunity to mobilize and bring people together. We were having sort

of a community meeting at Kucheh discussing how we want to show up to some of

the early protests here in D.C., what would be on the t-shirts, what were some of the

messages we wanted to elevate,” said Aghabozorg.

Aghabozorg also commented on some of the pushback from community members,

sharing that “our diaspora has a tendency to self-immolate, so it’s like, how do we

harness that fire for good? I think art is the best medium to do it.”

On a spring Saturday morning in Washington Circle, hundreds of protesters showed

up with signs that stated things like “Stop executions in Iran” and “Democracy in Iran

& Justice for All.” Although dedicated enough to show solidarity and shout slogans

alongside their compatriots, many do not want to give their names to journalists. They

don’t want to face harassment online or, worse yet, have family back in Iran be hauled

in for questioning.

For one Iranian-American, the backlash from her community has not stopped her from

voicing her opinions publicly.

Negar Mortazavi, an Iranian-American journalist and analyst, has been reporting on

Iran for over a decade – the most recent uprising being no exception.

“When the movement started in September, I was doing nonstop interviews as a guest

analyst for various international outlets. I’m an independent journalist and analyst. What I do is the intersection of reporting and analysis,” Mortazavi said.

Since arriving in the U.S. from Iran 21 years ago to attend college, Mortazavi has

been living in exile from her motherland since 2009, due to her political and media work. While

she has made a home for herself here in the U.S., harassment from her critics within

the Iranian diaspora community has complicated her identity as an Iranian-American

journalist.

“I’ve worked hard for years to be a fair and objective journalist, and I’ve paid a high price for my

professionalism and objectivity…to the point where people have called me a

mouthpiece for the regime,” Mortazavi explained.

Despite the regularity of the attacks she has faced, Mortazavi acknowledges that she

understands how individuals in the diaspora feel they have nowhere else to direct their

rage.

“When protests happen in Iran, the diaspora becomes very angry, naturally. And I

understand that anger. There has been an uptick in smears and attacks somehow trying

to scapegoat journalists and analysts like myself, especially those who are trying to do

objective, professional and fair work, to try to attach us to a violent brutal regime

who are killing children and women. Emotions are high, so we also get attacked by state actors and

psy-ops as well as members of the diaspora,” said Mortazavi.

Mortazavi believes that women journalists are especially targeted, and shared stories

of other Iranian-American reporters who have received similar verbal harassment

online, describing them as “a tsunami of attacks coming at us.”

Unfortunately for Mortazavi, the sharp increase in threats against her led to an account personifying “Anonymous” threatening an event where she was speaking at the University of Chicago, and the organizers receiving a bomb threat. Ultimately, the event was held on Zoom, but the emotional impact was felt heavily by Mortazavi.

“It adds much fear to an already stressful job – journalism itself, politics, and

working on a country and situations like this that are brutal. There’s a lot of killing, a

lot of violence…having to watch and then analyze killing children day after day is not

an easy job – and you can’t turn it off,” Mortazavi said.

While the attacks against Mortazavi have not ceased, she maintains a sense of hope

for her beloved homeland, crediting the courage of Iranian women for inspiring this

sentiment.

“I think this moment is an incredible time. We are witnessing a feminist uprising and a very progressive movement led by women and girls in Iran, bravely standing up to decades and centuries of patriarchy and political tyranny,” she said.

Jafari emphasizes the need for the community to fight less with one another and to

unify more.

“I just think that the attacks serve the patriarchy and the regime, so that’s the part

where I’m saying that the revolution is in our minds and hearts – that’s the shift we

need to see.”

Add comment