A D.C. Council committee will soon vote on whether the emergency police reform legislation passed in June should become permanent law in D.C., measures that some believe are not strong enough to reform the Metropolitan Police Department.

On June 10, in response to Black Lives Matters protests and a national outcry against police brutality, the council passed a temporary bill that banned the use of chokeholds by police, outlawed the use of tear gas against protesters and created the Police Reform Commission. The legislation remained in effect for 90 days, until Sept. 8, but organizations like Stop Police Terror Project DC argue that it changed nothing.

“The emergency bill supposedly banned the use of tear gas and other chemical weapons, yet D.C. police have repeatedly used them on protesters since the legislation was passed,” said Valerie Wexler, a spokesperson for SPTDC. “It even turned out that D.C. police had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to stockpile it.”

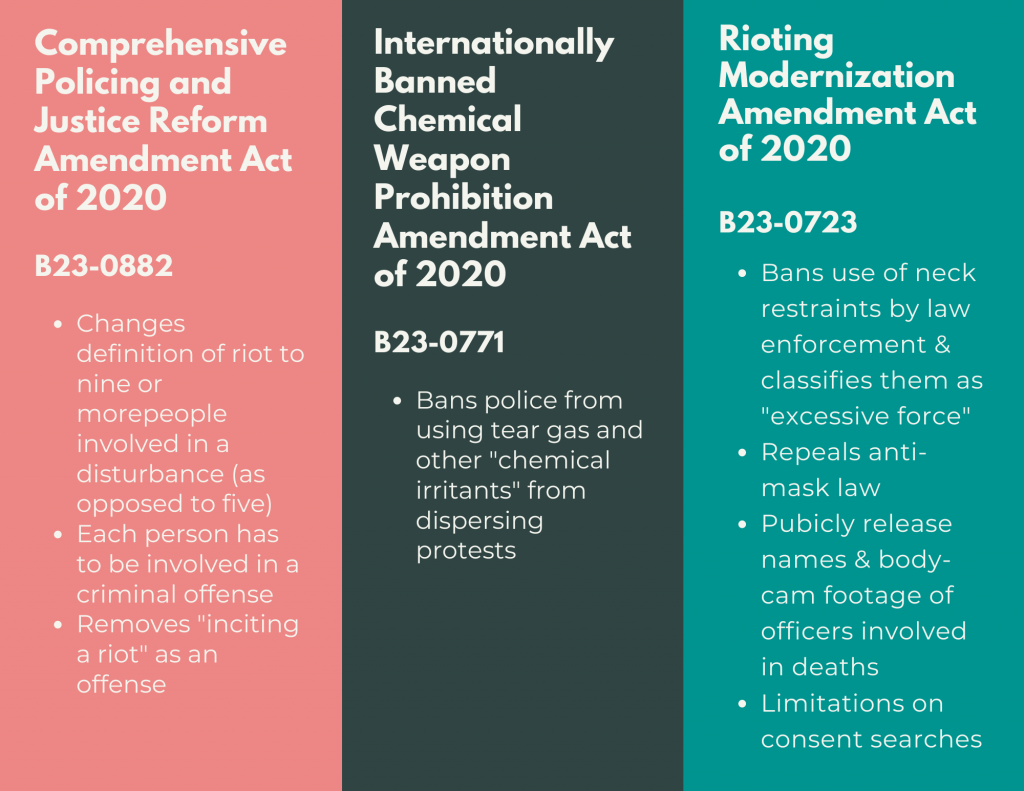

The D.C. Judiciary & Public Safety Committee held a public hearing Oct. 15 to consider three bills that offer more permanent iterations of the emergency legislation passed over the summer.

Patrice Sulton, founder of DC Justice Lab and committee member of the D.C Police Reform Commission, said legislators have “tremendous authority to limit police powers” but are not exercising the full extent of their oversight. She said the first step in real police reform is for the D.C. Council and other legislative bodies to fully utilize their authority over the MPD.

“It’s one thing to tinker around the edges and make suggestions about how the executive should train and discipline and recruit officers,” she said. “It’s another thing to say, ‘We’re going to regulate how you police because you’ve demonstrated over many years that you can’t figure out when it’s appropriate and when it’s not to stop someone, to search someone, to arrest someone, to violate someone.’”

Her project, More than a Plaza, proposes a number of reforms for the MPD to “go beyond mere performative gestures and do something meaningful about policing in the district.” Among them is a ban on drug raids, which she said are generally “ineffective” and overwhelmingly target Black residents.

“We have federal law enforcement that can step in if El Chapo comes to DC,” Sulton said. “We don’t really need state-level police doing drug raids at all.”

Mónica Palacio, a candidate for the D.C. Council at-large, said the legislation was a “great first step” in responding to the crises of the summer, but that more comprehensive laws are needed to “restructure and demilitarize policing.” The former director of the D.C. Office of Human Rights said the legislation should include stricter restrictions on the lethal use of force by police and create other crisis response agencies to handle emergencies.

“We just can’t keep adding bureaucracy on top of bureaucracy to solve the problems, we have to get to the core of police practices and standards,” Palacio said.

Ward 2 Councilmember Brooke Pinto said she supported the temporary legislation over the summer and is glad to see it considered as permanent law. She said it will bring necessary change regarding making body-worn-camera footage more accessible to victims and families, establishing independent police oversight bodies and limiting consent searches.

“This legislation is an important step and I am looking forward to receiving the recommendations of the Police Reform Commission to expand on these critical changes,” Pinto said in an email.

The bills will remain “under council review” until councilmembers vote on the legislation at the first reading of the bill.

Add comment