Brentwood resident Katie Bruckmann is Ms. Wheelchair DC. She lives in relatively accessible apartment complex, but just outside the building lies an unintentional obstacle course: the sidewalk.

“There’s this huge crack, and usually I pay attention, but a couple weeks ago I wasn’t,” Bruckmann said.

On her way to work, Bruckmann has to maneuver around a deep, wide crack in the middle of the sidewalk. It spans nearly the length of the full length of the sidewalk, as though someone had reached in and taken out a handful of concrete.

One day, she said, her wheels found their way to the bottom of that crack.

“I was texting, and not looking, and my front wheels went right in there,” she said. “I fell, hands and knees.”

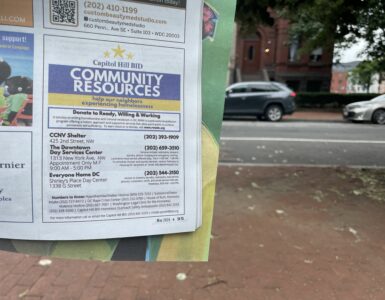

Many sidewalk users would never notice the crack, but for those who use mobility aids, sidewalks in disrepair can be the difference between a normal morning and slow, difficult or even painful commutes. In theory, the Americans with Disabilities Act prevents this problem with a few requirements for all sidewalks. Some of those standards include curb ramps for wheelchairs; raised bump pads near those curbs for those with visual impairments; and no cracks in which wheels could get stuck larger than half an inch across. In practice, however, many sidewalks have fallen into disrepair and no longer meet accessibility standards, with local governments doing little to address these problems.

The District Department of Transportation acknowledges some of these problems, and in 2016, they released an ADA Transition Plan. It opens with a promise: “The District Department of Transportation has a firm commitment not to discriminate against individuals with disabilities in its services, programs, or activities, and will honor and work to satisfy the requirements of Title I through V of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA).”

Despite the hope that plan provides, however, obstructions, cracks and missing ramps still litter the District’s 1,495 linear miles of sidewalks.

Data from University of Maryland-based accessibility application Project Sidewalk reveals that in Columbia Heights alone, there are nine missing sidewalks, 137 missing ramps, 38 surface problems and 434 obstacles.

Through the ADA Transition Plan and a variety of other goals, the District has clearly set out to make its sidewalks accessible—so why aren’t they?

The explanation lies with the Revised District Department of Transportation Sidewalk Installation Policy. In Section V. D. of this policy, it states the five conditions under which a sidewalk can be exempted from construction or installation: if it would be “unduly expensive,” if “would not be used by pedestrians,” if the director certifies it’s not needed for anyone (including children or disabled people), if it would damage parkland, or if it would require an easement of property.

At first glance, this section does appear account for those with disabilities because it tries to ensure the “safe travel” of all, with or without a sidewalk. On the ground, however, as data from Project Sidewalks shows, many of the District’s obstructed, cracked sidewalks are not actually accessible.

District residents and officials report that construction projects are a major issue resulting in missing or unusable sidewalks. South Glover Park Commissioner and transportation construction expert Brian Turmail stresses the importance of maintenance and upkeep.

“The city has got to be a lot better at saying, ‘Look. If you’re going to cut up a sidewalk, you’ve got to bring it back up to the same condition it was in when you started,’” Turmail said.

Southeast neighborhood Hillcrest is one of the worst neighborhoods for District mobility aid users, data from Project Sidewalk suggests. In this neighborhood alone, there are hundreds of mobility obstacles.

Longtime Hillcrest residents Kathy Chamberlain and Cathy Keen walk their neighborhood daily for both exercise and to pick up trash on the road. At this point, they say their concerns are less about obstructed or cracked sidewalks and more on not having sidewalks at all in many places.

After a variety of construction projects wrapped up on Hillcrest streets, Chamberlain explained, several sidewalks were just never rebuilt.

On a tour of the neighborhood, Chamberlain and Keen pointed out a spot without a sidewalk, the path of which would be obscured by large tree.

“If you were in a wheelchair here, the tree trunk, or tree roots rather, would get in the way,” she said. “Now they might say ‘Oh, we can’t put a sidewalk here because there’s a tree.’ I don’t think you have to take the tree down. There are ways to work around trees.”

This is not the first time DDOT has been in the spotlight accessibility issues. Multiple District residents have asked DDOT about the problem on social media to no response.

The DDOT ADA Transition Plan seems to account for these issues, but it has yet to be updated. The plan accounts for several accessibility improvements, but has not been updated since 2016. The plan aimed to hold “ADA Compliance Counts” workshops, a grievance program and an advisory group comprised of community members from across the District and across ability levels, but by 2017 the Transition Plan seemed to have fallen by the wayside.

DDOT ADA Coordinator Cesar Barreto has yet to respond to requests for comment.

The ambitious ADA Transition Plan specifically called for a self-evaluation of the District’s accessibility issues, “primarily focusing on sidewalks, crosswalks, curb ramps, accessible pedestrian signals and bus stops.” Today, however, DC 311 data still shows the disparity for individuals with disabilities. Between October 2 and November 2, 2019, over 350 sidewalk-based work requests were submitted through 311.

A few bumps in the road may seem insignificant, but for those who rely on mobility aids, the time and energy spent maneuvering those cracks and bumps in the District’s sidewalks is crucial. For Bruckmann, these broken sidewalks she maneuvers on her commute are not just daily struggles. They also serve as a reminder of how local governments repeatedly fail disabled individuals.

“We have the ADA. And it’s put in place. . . kind of,” she explained. “Bare minimum, in a lot of places. And part of that is not only making sidewalks accessible, but the upkeep of them.”

Add comment