Melanie Adams believes art education may be a way to fill more of the empty seats in classrooms, but for that to happen in D.C., the school system needs more art educators who are Black.

“Sometimes it’s things like art and music that get kids to come to school, when they know that they’re going to have art class or they know they’re going to have music class,” she said this past Saturday at a panel discussion sponsored by the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum.

“We want people to see themselves… sometimes people just don’t recognize their rich history in their own community because they’re so used to it,” Adams said.

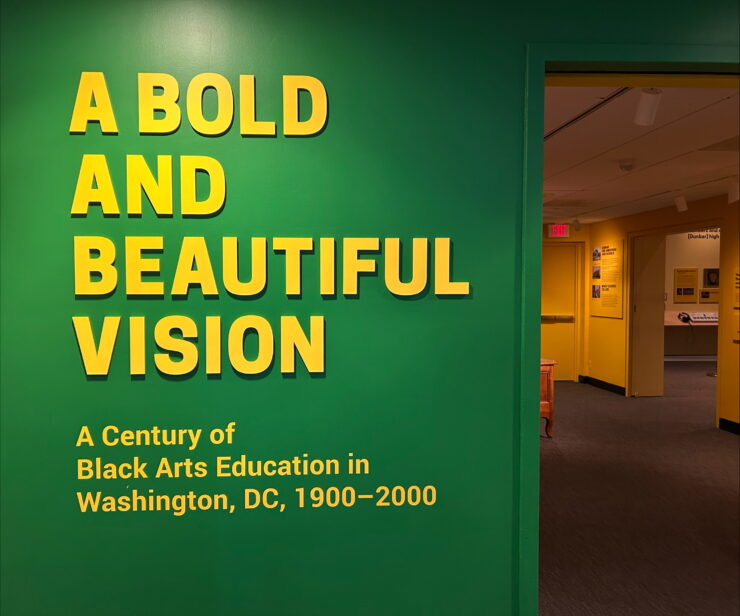

Adams is the director of the museum, which is showcasing an exhibition titled, A Bold and Beautiful Vision: A Century of Black Arts Education in Washington, DC, 1900-2000. The museum hosted the discussion panel in an exhibit led by art educators, where community members joined in conversation about how art became integrated in the Black education system and how much it’s still needed today.

Adams said she hopes the exhibit will serve as a call to action, to reignite the value of Black art education, with features of 20th century art educators, original artwork and artifacts of Washington.

Panelist Dr. Pamela Harris Lawton comes from a long line of educators in her family, starting with her great-great grandmother who was part of the first 50 Black teachers hired in D.C.

A lineage of educators

Lawton’s mother and grandmother continued the lineage of educators, though Lawton didn’t immediately follow in their footsteps.

“I will be completely transparent and say the last thing I wanted to be was a teacher,” she said. But it wasn’t until she was 36 that she realized her desire was to be an art educator.

As the first art educator in her family, she taught in several college classrooms and currently serves as the chair in art education at Maryland Institute College of Art.

But the trajectory of her career shifted when a friend of hers asked if she knew anything about art education for Black students during segregation in D.C.

“I did not know, because none of my family were art teachers,” Lawton said.

But Lawton said she could still piece together some answers through her family, beginning with a painting of her great-great grandmother that hung above the organ in her grandma’s house.

Lawton discovered the portrait of her foremother was painted by an artist named Thomas W. Hunster, who she found out to be her great-great grandmother’s art teacher.

“He created the art education system here,” Lawton said. “He taught elementary school teachers how to draw so they could teach drawing to their students… they weren’t art teachers, but they included drawing in the curriculum.”

Hunster, for whom researchers have no images but only a description of being “blond haired and blue eyed,” taught art to Black teachers in the 1890s when segregation was the norm in the district.

According to Lawton’s panel presentation, an increasing number of African Americans became art educators in the 20thcentury, and it became evident that students of color were highly engaged in the art learning process. But that zeal for art doesn’t hold up quite the same in present-day classrooms.

“I think one of the things that I’m pushing for is for more Black folks to go into teaching, that’s one thing,” Lawton said. “Where is the color in our education? Because you don’t see us. And so, what happens is when you don’t see yourself in the teacher, you don’t think about being the teacher.”

African American art professors are not given a fair chance

Dr. Debra Ambush, another panelist, said that “African American art education professors are not really given a fair chance” in the landscape of teaching.

Ambush is an independent scholar who has taught art for decades and has developed a theory around the development of Black aesthetics in art education.

“The first art education occurs on our bodies,” Ambush said. “We must be interpreted in colonial America, we are classified by our dress, our status as enslaved and free, and so it made sense to me to talk about this formulating art education as foundational mechanisms for cultural intervision.”

Ambush grew up in the 60s during the “slow thaw of segregated Washington” and was part of the integration process of Montgomery County Public Schools when she was in the 4th grade.

The educators who preceded Ambush fought against countless obstacles just to teach art in their classroom, and Ambush identified curriculum accreditation as a “major block way” a tactic used for “testing and all the impediments that we have,” she said.

Curriculum accreditation is a method used to ensure the material being taught to students are skills they need to learn. But this system is bound to be subjective, and Ambush said it can “deny us full sovereignty in our art education endeavors.”

Broadening how art is shown

The teaching of art in schools often reflects a Eurocentric perspective, and Ambush said that art has to be shown in more ways than one.

“We must consider in the discussion of African American art and [its] educators [what] their motivations [are] for seeking out a profession that puts the discussion of beauty in their hands,” Ambush said.

Pearl Eni sat in the front row at the panel discussion, and as an educator herself, said she aims to use spaces like museums to “turn the world into a living classroom” for her students. While Eni doesn’t teach in a formal school, she seeks opportunities to teach children different subjects and said many of their core principles weave in together one way or another.

“When I’m teaching lessons on physics, for example… the children love to make paper planes. That’s a physics lesson, but that’s also art,” she said.

Eni described the panel discussion as “an honor” to sit in on and said she finds educators to be “just really beautiful people [and] very generous spirits.”

To revive the passion for art in younger generations, Ambush said more barriers need to be dismantled to get Black art educators back in the school system.

“It’s a spiritual fight. I think it’s a fight of resistance,” Ambush said. “I think that requires honest dialogues among each other, first, the commitment to get together.”

Love this info!

Great article! This is an important topic that doesn’t get much attention. I love the history that was included. Great job!

[…] D.C Needs Black Art Educators, and Its History Proves It The Wash (American University) […]

[…] D.C Needs Black Art Educators, and Its History Proves It The Wash (American University) […]