A Black town erased by the construction of the Pentagon will be remembered through art in Amazon’s new Metropolitan Park in National Landing.

After over two years of construction, Metropolitan Park is expected to open up in May, along with a 30-foot above-ground well designed by local artist Nekisha Durrett to honor the Black neighborhood of Queen City.

The well will be covered in red bricks and will spell out Queen City in large letters through the bricks on the outside.

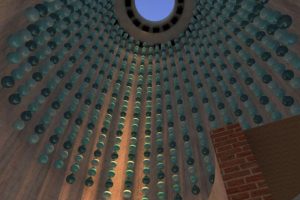

Viewers will be able to walk inside during the daytime and see the 903 green handmade ceramic vessels covering the walls of the monument.

In the evening, the door shuts but a glass pane will allow visitors to still see the inside. Etched into the glass will be a brief description of the project.

The construction of Metropolitan Park is part of Amazon’s first phase of its 10-year $2.5 billion development commitment to National Landing.

Along with the monument, the park will include a 700-person event space and a total of 8,800 square feet of open lawn, according to a Nov. 15, 2021 infographic of the park.

The park will include two other pieces of art, one from Spanish artist Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle and another from Canadian artist Aurora Robson.

The three artists were among many others tasked with submitting a proposal of what they wished to add to the park.

Based on those submissions, Amazon chose these three artists.

When the opportunity came, the first thing Durrett said she did was Google Black History in Arlington.

Queen City “pops right up,” Durrett said.

Durrett is no stranger to capturing Black stories in art as her mural of James Baldwin was in the National Portrait Gallery as part of the Outwin competition in 2019.

Her piece Magnolia brings awareness to Black women and girls who have been victimized by racist police violence, a group Durrett said is constantly overlooked.

The community of Queen City was destroyed in 1942 to create the cloverleaf highway structure that allowed workers living in D.C. to be able to drive to the Pentagon, according to historian Dr. Nancy Perry in a lecture to the Arlington Historical Society.

Before its destruction, Queen City residents were denied running water, sewer pipes, and paved streets by Arlington County, according to Perry.

Even lacking those necessities, Queen City was said to be a thriving community, according to an article published in the Evening Star on Jan. 26, 1908, with the headline “Negros solve the problem of peaceful living.”

“A spirit closely akin to communalism reigns in (this) town,” the author wrote.

A total of 903 residents watched the construction of the Pentagon occur from their windows, until February 1942 when they were notified that they had only three weeks to leave their homes for good, according to Perry.

Durrett honors each individual by commissioning professional ceramists to create the 903 handmade ceramic vessels that will be on the inside of the monument.

“Every piece is almost like taking up space,” Durrett said. “Not just taking up space for me, but taking up space for people who can’t take up space for themselves.”

This reality hit home for Durrett.

Durrett’s grandmother was living in Orange County, Virginia as a child when her family was forced to migrate to upstate New York.

When evacuated, less than 600 Queen City residents were able to live in the George Washington Carver Cooperative apartments. The rest had no choice but to travel all across the country to find distant relatives that were willing to take them in, according to Claire Burke’s graduate research at Mary Washington College in 2004.

“I want people to encounter this thing that looks perhaps like something they’ve seen before,” Durrett said. “Perhaps like something that looks like it’s serving some kind of utilitarian purpose, but that looks kind of jarringly out of place.”

Hannah Murphy, a resident in BridgeStreet apartments right across from the park, thought just that.

“I have no clue what it’s supposed to be,” Murphy said. “It’s interesting that it’s going to turn out as an art installation. I would have never thought that.”

The monument still has a ways to go until it is set to be complete in May.

In the next coming months, the monument will begin to look a lot different as the red bricks are added.

Durrett decided to use brick to recognize the history of Arlington.

Arlington was one of the largest distributors of brick in the U.S. during the time Queen City existed. One of Virginia’s largest brickyards, West Brothers Brickyard was also destroyed along with Queen City and the Hoover Airport to build the Pentagon, according to Perry.

According to the 1940 census data, 38% of adult men living in Queen City worked at that brickyard.

Although Durrett is including history along with the artwork, she doesn’t want it to come off as a museum exhibit.

“What I’m going for is more of an emotional response,” Durrett said. “I am trying to bring forward the history of this little-known community.”

Durrett does plan to add access points for further information about Queen City to the monument.

“I’m glad Queen City is starting to get the recognition it deserves,” John Stanton, Historical Research Associate for the Center for Local History at Arlington Public Library, said.

For more information, visit the Center for Local History at Arlington Public Library.

An Amazon spokesperson was not available for comment.

Add comment